Kinaz and her baby Roj haven’t been out of the house since New Year’s. First it was because of the winter cold. Now, it’s because of the coronavirus. Kinaz’s husband Arjan is afraid of his family getting sick. He tells us whenever they take Roj out, there is always a crowd of people wanting to kiss him or pinch his cheeks.

Even in a Syrian refugee camp for those displaced by war, coronavirus is on everyone’s mind.

Text “CV UPDATES” to 72000 to get the latest on the coronavirus and how it’s affecting our work.

As the number of coronavirus cases grow worldwide—including in many of the places we serve—we’re checking in with our refugee friends. Refugees and displaced families the world over are hit particularly hard by widespread crises like this one.

Here’s how the coronavirus (or COVID-19) outbreak is impacting our displaced and vulnerable friends around the world.

Refugees in Iraq

Refugees in northwest Iraq (near the border with Syria and Turkey), aren’t yet overly concerned about getting sick—but they are taking every precaution possible.

Schools are closed, so children are staying at home. No one goes out to busy places unless they absolutely have to. They clean and sanitize their houses every day. In refugee camps, houses are tiny, and families have few possessions, so the task is manageable.

But for families cooped up in a couple cinderblock rooms for weeks—it’s tough.

At refugee camps in northeastern Iraq, near the border with Iran, concerns over coronavirus are much stronger. Iran has become one of the epicenters of the virus, with thousands of cases so far.

What you may not know is that ties between Iran and Iraq are especially strong. Family members, commercial goods and produce, Islamic studies students, and politicians regularly cross the border from one country to the other.

Normally, this traffic is a good sign, economically and politically. Now, it’s a huge cause for concern. Every one of Iraq’s confirmed cases of infection so far are recent visitors to Iran.

The risk of transmission is changing the daily pattern of life for refugees in northeast Iraq.

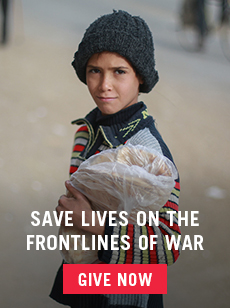

Arjan (pictured above with his family) examines the food he buys much more closely—no products from Iran. He regularly wears gloves now, whether taking a taxi or handling money.

Arjan works the reception desk at one of our four tech hubs in Iraq. He now keeps two pens handy—one for visitors and one for him.

“When I take care of myself, I take care of my family, too.”

For another refugee friend, Nalin, facing coronavirus while living in a camp triggers fear for her children. Since the schools closed down, she has kept her children home. She’s afraid for them to visit the homes of other children in the camp, unsure that they take as many precautions as she does.

The family’s pattern of shopping and eating has changed dramatically. Nalin used to go to the market every two days to shop for fresh food for her family. Now, fresh food that’s been handled by people has lost its appeal.

She’s buying more at one time, to reduce her exposure to neighbors outside her home. And she’s no longer buying fresh food. Instead, she’s stocking her shelves with shelf-stable canned and packaged food—processed by machines.

Our refugee friends in Iraq have one advantage over vulnerable people elsewhere: they have better access to healthcare, and they have some stability. Both factors mean they have a better chance to fight viruses and disease.

That’s not the case in some of the other places we serve.

Displaced families in Syria

No confirmed cases of coronavirus have been reported in Syria yet, but if the virus reaches there, it will be a disaster for displaced families.

Officials at the land borders with northern Iraq are testing temperatures of those wishing to cross. Once symptomatic, patients with coronavirus develop a tell-tale fever. At least one of the border crossings between Syria and Iraq is closed, except to aid workers, who are potentially allowed in just one day a week.

This will dramatically reduce the amount of aid able to reach families in the country’s northeast, who were forced from their homes when Turkey began military actions in the area.

Millions of displaced families in Syria are at high risk. They are chronically exhausted from years of living in survival mode. Many are malnourished. Continuous exposure to cold and rain have compromised their immune systems, and they are living in close quarters with each other

In other words, they are living in the perfect conditions for disease to spread quickly.

In addition, so many of Syria’s hospitals in zones of conflict have been bombed. There is simply no healthcare available for those who fall sick.

And for displaced those fleeing Idlib toward the Turkish border, who have yet to find a safe place to stay, the conventional means to stop the spread of disease are impossible. How do you wash your hands frequently when you have no source of water? To do the things we know helps, is a luxury much of the world can’t afford.

Migrant families in Mexico

To date there are three confirmed cases of the coronavirus in Mexico, all men who recently returned from visits to Italy.

Migrant families living in shelters near the border of the United States face many of the same challenges as displaced families in the Middle East. Many are living in overcrowded conditions, in rooms filled with bunk beds. Many are exhausted and eating nutritionally poor diets, which can weaken immune systems. Coronavirus would spread through most shelters in a flash.

The United States government is said to be considering measures to further tighten access to the country from the southern border, in order to address fears about coronavirus traveling north with cross-border traffic.

At the present, the larger concern should be for those hopeful migrants who have already entered the United States, and are being held in crowded detention centers. Access to healthcare has been an issue in some facilities, and the living conditions are much the same as for refugees anywhere—perfect for the spread of disease.

“Boomerang Migrants” in Venezuela

The migrant community in Venezuela is unique in many ways. There are families who have left home and fled to nearby countries, unable to survive in the depressed economy, violence, and volatility of their home country. But there are also a number of vulnerable people known as “boomerang migrants.”

These are Venezuelans who don’t want to leave home. They are trying everything they can to stay in the land of their birth. Venezuela cannot supply the work, funds, or food they need in order to stay, so some risk crossing illegally into Colombia to the west, in order to receive emergency aid—food and basic healthcare—and then return home to Venezuela.

The crossing is highly dangerous—many women are forced to pay with their bodies if they don’t have viable currency to pay their way across the border. The Venezuelan currency has so little value now that it is useless outside the country.

Neither Venezuela or Colombia have any confirmed cases of coronavirus, but Colombia does have suspected cases.

Any cases of coronavirus that enter the migrant population would spread rapidly through both countries. For Venezuelans, whose healthcare system is already devastated by years of internal crisis, there is little to no chance of receiving adequate care.

Outlook for Refugee Families Worldwide

For families who were forced to leave home months or years ago, they’ve had time to recover a little. They expect the near future to be inconvenient, and very expensive—many will lose days of work as municipalities close gathering places like cafes and restaurants, where refugees often find work.

They are resigned to fate, even if it means death. In the words of our Iraqi teammate Ihsan, “Death has been with us for a long time now. The idea of a virus killing us is no new thing. If it starts to happen here, then it’s just like any other day in Iraq. You know, death has been taking a lot of people—more than any virus. Violence has infected the community more than any virus in the world.”

We continue to stand with our refugee friends. We continue to listen to their most pressing needs. And we’re delivering the kinds of aid that reduce their vulnerability: food and warm clothes to help immunity, mobile health clinics in places where healthcare is absent, and jobs that bring stability.