Memories live in our bodies long before we can recognize them.

I MET SARAH* when she was fifteen. By then, she had lived a lifetime. With dark hair and eyes, quick wit, and a laugh that rumbled all the way from her toes right out her eyes, she was the most popular girl (and renowned storyteller) at the group home.

Sarah had grown up in a big Midwest family—some of her best stories were about adventures with her mother and siblings. But she was born in eastern Europe during the Balkan Wars, and her birth parents were forced to flee their home country as refugees when she was an infant.

Sarah had grown up in a big Midwest family—some of her best stories were about adventures with her mother and siblings. But she was born in eastern Europe during the Balkan Wars, and her birth parents were forced to flee their home country as refugees when she was an infant.

They feared that without food or shelter, they couldn’t keep their child alive. So to ensure her survival, Sarah’s parents brought their baby to a crowded orphanage where she was fed and clothed, but received very little attention. At the group home where I met her, Sarah never told the girls stories about her orphanage—she was adopted by an American family as a toddler, and she said she had no memories of her former life.

But memories live in our bodies long before we can recognize them.

Relationships are the agents of change and the most powerful therapy is human love.

Dr. Bruce Perry

Sarah’s first years of life were full of struggle and pain. Born into a world of bombs and bullets, she was brought to safety by parents who loved her, but were forced to leave her. With few staff caring for dozens of small children in the orphanage, Sarah learned that she could cry, but no one was coming to get her.

By the time she was in grade school, Sarah had been labeled a troubled child. She had temper tantrums and screamed at her family. She had learning setbacks and didn’t play well with other children. She demanded attention through bad behavior—stealing, lying, and fighting with the people closest to her.

When she became an uncontrollable teenager, Sarah was sent to a group home where she could receive intensive therapy for exposure to trauma. It was at this home that Sarah learned that her feelings and behavior weren’t abnormal for her circumstances—in fact, they were expected.

Sarah may not remember life as a baby, but she was altered by it.

From behavior disorders to early onset cardiovascular disease to cycles of family and community violence, traumatic experiences are woven into the very fabric of our lives.

*Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Chapter 2: The Effects of Trauma

The antidote to the effects of trauma is exactly what we’ve known in our hearts is the path to healing: connection.

EVEN BEFORE WE are born, our relationships and experiences impact who we are and who we are becoming. As we grow in the womb of the woman who brings us into the world, our biology knows her—what she eats, when she sleeps, whether she is carefree or stressed, whether others show her love or abuse—and it responds.

Before we know the world, we are preparing for it.

As our bodies develop from fetus to infant to child to adult, our brains develop, too. Our experiences impact—and at times, control—that development. In the same way that hearing the loving voice of a parent speaking teaches us that words have meaning, the things we see and feel as a child teach our brains that everything else in the world has meaning, too.

Those children that grow up in safe and nurturing environments tend to believe they will be cared for, that their world is a protective place for them to grow. But children who grow up in highly stressful environments—in abusive homes, in war zones like Syria or Iraq, or even in communities where violence is prevalent—often learn instead that the world is a dangerous place, where they must be vigilant, learn to protect themselves, and always look out for the danger that might be hiding around the next corner.

Trauma—deeply distressing or life-threatening situations—causes our brains to release high volumes of stress chemicals. In many situations, these stress chemicals are good—they tell us when something is wrong and help us respond quickly to danger. If you are crossing a street and hear a car loudly blasting its horn, you want your brain to tell you to quickly move out of its way! Our stress responses are meant to keep us safe.

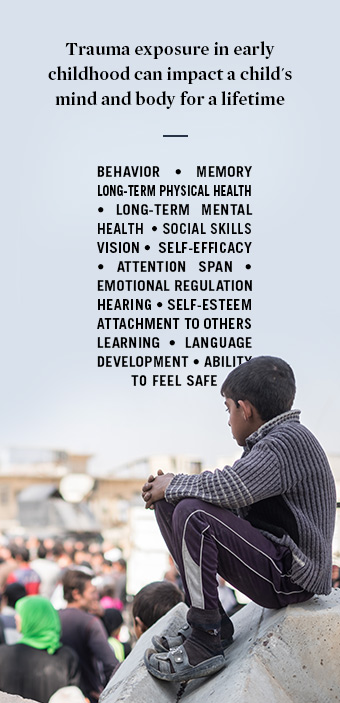

But too many stress chemicals over a long period of time can be toxic, especially to the developing brains of small children. As we age, the different growing parts of our brains are impacted uniquely by traumatic events. These experiences can impact nearly every part of a child’s mind and body—from behavior and social skills to vision and hearing to learning and memory to the ability to feeling happy.

Traumatic experiences have a distinct and jarring ability to alter the way a child learns, plays, and grows.

And it doesn’t stop with childhood. Since a child’s brain is the foundation for an adult’s brain, trauma can translate to a lifetime of health and social issues. In fact, one of the largest public health studies ever done in the United States recently provided the scientific evidence to confirm what we long suspected: trauma in early childhood is directly linked to a multitude of mental, physical, and social health challenges for adults.

We must dare to imagine a more beautiful world for our children, and for us.

From behavior disorders to early-onset cardiovascular disease to cycles of family and community violence, traumatic experiences are woven into the very fabric of our lives.

Simply put, trauma itself can act like a disease, beginning in the brain of a small child and winding its way through the body, the family, and eventually the community. While trauma isn’t a diagnosis or a life sentence, it’s certainly a good predictor of suffering for the smallest of us and the people they grow up to be.

But even in the darkest places, there is hope.

When things seem too hard, we look to love. And as it turns out, love is the answer – or part of it, anyway. The antidote to the effects of trauma is exactly what we’ve known in our hearts is the path to healing: connection.

Loving relationships and compassionate interactions can act as protective mechanisms against the impact of trauma. Where traumatic stress interrupts development, nurturing connection makes brains stronger and healthier. In fact, support from caring adults may be the single most important factor in a child’s recovery from trauma-induced mental injury.

For children to be able to think and grow, they need safety. Sometimes, safety looks like relationships that provide security and a sense of belonging. Children born into safe, secure, and loving environments develop brains that aren’t as vulnerable to trauma – they often aren’t as impacted by hardship as those without supportive surroundings.

Loving connection can be a lifeline even in the midst of hard things. For example, children exposed to persistent violence in their homes but also with a loving parent who hugs them, sings to them, and helps them learn new skills have been shown to be physically healthier than children in the same situation without a nurturing adult figure.

We can’t always stop war or domestic violence or painful losses from happening, but we can provide the kinds of loving interactions that children need to buffer some of

the negative effects of terrifying experiences. Caring connections both protect and repair developing brains.

Resilience—the ability to thrive even in the face of painful experiences—is a characteristic we hope for children to build. Resilience is what keeps us going despite hardships, whether it’s the loss of a job, recovering from a natural disaster, or the struggles faced in a displacement camp.

And at the heart of resilience is relationship—connection with someone who cares about your wellbeing. Loving and safe environments aren’t just nice things for kids to have; they’re necessary for a child to thrive. They are the building blocks of the resilience that cultivates healthy childhoods.

So what does childhood trauma have to do with peacemaking in places like Iraq and Syria?

We can’t always stop war or domestic violence or painful losses from happening, but we can provide the kinds of loving interactions that children need to buffer some of the negative effects of terrifying experiences.

And with mounting evidence that the impact of trauma can live on in our DNA, we are forced to reckon with the idea that the wars of today are carried on in the bodies and minds of the next generation, and the next.

To heal our world, we must heal our children.

We know that healing can start with connection. Of course, it’s not the only answer—but it’s a first step toward resculpting minds and bodies that can flourish. When we invest in healthy childhoods for all children—in the US, Iraq, Syria, and around the globe—we are working together to unmake violence and create the more beautiful world our hearts long for.

Chapter 3: A Space for Kids

What will become of a generation of children, traumatized and forgotten?

THERE’S A REFUGEE camp in northeastern Iraq that’s home to nearly 9,000 Syrians forced to flee their homeland.

This refugee camp was never meant to be home. But for years, it has housed thousands of refugees, half of whom are children. They came to escape horrific violence from militaries, terror groups… and for some, even their own families.

The camp is not a very warm and welcoming place. It was built for emergency response—not a nested community. But with the Syrian war still raging, there is no going home today, tomorrow, or for the foreseeable future.

To heal our world, we must heal our children.

Every child should have a safe and happy start to life. But for children here in camp, the innocent and carefree childhood they deserve has been ripped apart by war and its devastating consequences. Living in the camp, children and their parents are not only separated from their homes, but from the neighborhood friendships and tightly knit family networks that once formed their support systems.

For the thousands of children and their parents here, camp is a safer place than home. But it doesn’t always feel that way. Broken by the betrayal of systems that were supposed to protect them and the horrific violence witnessed in places once sacred, traumatized families live with guardedness and vigilance.

In the camp, the smallest people have already faced some of the biggest hurts. As refugee children cope with unimaginable fear and grief from the trauma of a war they can’t possibly understand, they are also vulnerable to exploitation, assault, and isolation here in the refugee camp.

Parents warn their children not to go outside, because they’re afraid of what might happen if they do. Kidnapping, gang violence, or perhaps something worse? These weary parents have already lived a nightmare; they can’t live it all over again.

What parent wouldn’t be afraid?

But children can’t be children without the space to run and play and create. And the open wounds of war—wired into their biology—won’t be mended without the security of a safe and nurturing environment, and caring adults who are able to invest in their healing.

Support from caring adults may be the single most important factor in a child’s recovery from trauma-induced mental injury.

What will become of a generation of children, traumatized and forgotten? And what will become of the children of these children, bombed-out and raised in the shadow of war? And what of the generation after that? In some places in the world, an endless cycle of trauma and violence isn’t hard to imagine.

That’s where you come in.

There is a place in this camp that offers children safety, a chance to play and learn, a chance for refugee kids to simply be kids, to heal from the trauma of war.

Tucked beyond rows of functional, concrete camp structures is a different kind of building—a place where a kind of magic happens. In the comfort of this space filled with friendly staff, child survivors of war can just be kids.

They can come alone—to simply be loved and play safely with other children, or talk with trained professionals about hard experiences. They can also come with their families and be given tools to heal and build resilience together.

Here, kids are encouraged to create art, learn games, and play with one another, all while processing trauma in the care of social workers and trained staff.

Trauma treatment can be difficult and painful work. But in this space, that’s not what it looks like.

Kids can process suffering and loss through self-expression, designing and creating art with the support of a therapist who gives them space to draw, paint, and process their pain.

Children can recognize that they are not powerless by learning to rock climb, with caring adults to believe in them, guide them, show them they are capable, and keep them safe.

Teens in the camp can begin to develop leadership skills with the center’s staff who nurture them and challenge them to mold their pain into passion. In the leadership program, refugee teens envision ways to lead their communities with the love and wisdom that facilitates peace.

Wherever we go, we fight for the smallest of us—not with guns or chemical warfare—but with compassion and revolutionary love.

It starts with healing relationships with adults in the safety of the center for kids, but it doesn’t stop there. As they create, climb, practice leadership, and engage in a multitude of other activities, therapists and trained staff are guiding children into deeper therapeutic work. They are building on their authentic connections to these children to help repair and restore their minds, bodies, and souls. To build resilience, so they are stronger and healthier moving forward.

And we stand with parents. Because healthier parents are better parents, who can invest in raising healthier kids.

We know emergency aid alone can’t heal the deep wounds of war. And healing can’t happen in an instant. It takes time and connection and love—love that is willing to stick around long after the bombs stop falling.

Love that is first in, but also last to leave.

Children in refugee camps and other places devastated by violence may be a few man-made borders away from us, but they still belong to us. (We belong to each other, after all.) And we fight for our children—for our babies opening new eyes to this world and for our restless teenagers, who’ve known only a life of war they didn’t start or deserve.

We fight for the smallest of us—not with guns or chemical warfare—but with compassion and revolutionary love. We fight by making their world a little better, a little safer, a little more like home.

We may not always see clearly the long and winding road to peace, but we know where it starts—with our children. We must dare to imagine a more beautiful world for them, and for us.

We’re imagining happy, healthy childhoods—even in the wake of destruction. We’re imagining life that grows through healing relationships. We’re imagining a new future—one where communities frozen by terror and loss are transformed into thriving communities as their youngest members blossom and flourish.

Will you join us?

Editor’s note: This post was originally published on October 9, 2018.