This year, for World Refugee Day on June 20, we invite you to step into the shoes of your refugee brothers and sisters by sharing a Syrian-inspired meal with your friends and family.

In the final piece of this article—after we explore Syria’s rich cultural cuisine before and during the seven-year conflict—you’ll find resources and practical ideas for hosting a dinner party in recognition of World Refugee Day. We’ve created everything you need to make it a success, from invitations and recipe cards, musical playlists, conversation starters, and much much more.

We hope you’ll join us on June 20, and that it will lead you deeper into empathy and understanding of those who have been forced to flee violence.

![]()

“In Syria, nobody drinks their morning coffee alone.”

“Your neighbor will even invite you to coffee, or you will invite them to coffee every day.”

My friend Azad sits to my left at a table on his wide balcony. It’s long past dark, the early summer air is warm, and the sound from the shops on the nearby street creates a steady background buzz.

Azad’s mother and wife sit with us. His young son moves around the table from lap to lap.

“People come and visit a lot,” he says referring to his former life in Syria.

“Sometimes you’re at your balcony and some of your friends or people you know pass, and you say ‘Hey, come have a coffee’. It’s a very good thing.”

Azad is animated as he speaks, hands waving, smile wide. He has lived in Iraq since early in the war, before his hometown Aleppo was destroyed by violence. Yet when he speaks of his old life in Syria, he still uses the present tense.

“Of course, in Aleppo… the cuisine is so rich. They have so many dishes, unlike here. We didn’t used to eat the same dish daily. We don’t even know how that can work. Sometimes if my mother cooked the same meal twice in a month, we will say ‘C’mon! We already ate it this month!’

“In Aleppo… they put so much concentration and so much effort on food. They enjoy the food. They make it very well.”

Home Cooking

“Sometimes in [traditional] families, when they used to marry someone, one of the main questions was, ‘Do you cook well?’ ”

Azad’s mother, Sheraz, learned to cook at home from her mother when she was 15 years old. After she married at 19, Sheraz learned to make her new husband’s favourite dishes from his mother, also a very good cook.

Food played a central role in Sheraz’s life. She studied to be an electrical engineer, and later a lawyer, but there was always time to think about the dishes she would serve her family.

“We have a very rich breakfast. They prepare a lot of things… it’s huge. The table is so rich, because we have so many things.

Nobody drinks the coffee alone. We don’t do things alone. I really love it. It’s like a magical thing.

“Of course the ful—the broad beans and tahini—it’s kind of like the Friday ritual. At breakfast you have that. And of course we have mamoniya too. It’s crushed wheat, and they fry it with sugar and butter. It’s a very ‘Aleppo Friday ritual’ thing. First we eat the ful, and then move to the sweet thing. And we eat that with cheese—a salty cheese… and you won’t be hungry for like a week.”

Azad’s immediate family lived in Aleppo for 70 years but came from Afrin in northwestern Syria before that. His family traces their time in Afrin back 350 years and to Turkey before that. A war with the ruling Ottomans sent his family into Syria, and the current war sent them to Iraq.

I ask what dishes they cook when they’re missing home. “Everything. Because all our dishes are different from here.”

“They have this thing in Aleppo City, it’s a very classic dish, with [natural casing], and they put rice, pistachios, ground meat, spices…”

He describes what is essentially a short, rice-based sausage. “They put it in the oven so it’s sort of crunchy. Or you can boil it. It’s more like a winter dish.”

“When it’s so hot [in the summer]… we do a lot of onion, tomato, olive oil, and something else with that. Eggplants… And when we eat, we cannot eat meat without salads. In Syria, if you give just meat to someone, they won’t even eat it. Not without the stuff that comes with it. The salads, the appetizers.”

One of Azad’s favourite dishes is his mother’s kibbeh. And for Sheraz, it’s her favourite thing to cook. A type of stuffed, fried croquette, she makes hers about as long as your index finger and football-shaped.

Sheraz makes a dough from bulgur, pinches off portions and forms them into shells that hold ground meat, walnuts, onion, and spices. The shell is stuffed and formed into a football shape and fried. The filling is a place for creativity, they tell me. In his family, they sometimes add sour pomegranate seeds—the flavour mixes very well with the meat (see their family recipe below.) Azad prefers his Mom’s kibbeh to any other.

In the winter, they prepare a flatter, disc-shaped kibbeh, filled with fatty meat, and cooked over a grill. The kibbeh is deemed good if the juices run down your chin when you eat it.

“You have to eat it only in the winter. You have to be cold, and need a lot of energy.”

Restaurant Culture

“You know, the hamburgers and the pizza—they’re not so popular. Because we have more delicious things.”

When Azad first moved to Iraq, he worked in restaurants to support his family. He knew a particular food culture growing up in Syria. He learned different approaches to food while working in Iraqi restaurants, serving foreign customers.

“In Syria, people had a really long time to develop dishes, and to come up with things. Since the Ottoman Empire [1453], they didn’t really have war. It’s a very old civilization. In Aleppo City, we have bazaars that are like…I don’t know…2,000 years old. They were destroyed, in the last few years…”

“When people are just trying to save their lives, they won’t focus too much on developing different kinds of bread, you know?”

But before the war, the situation in Syria was entirely different.

“The dishes are so many. No restaurant in Aleppo City could offer the whole cuisine—because they can’t. It’s too much. So they specialized.”

“In Aleppo City, it’s famous for its appetizers. One of the appetizers is [a sweet and hot pepper paste], with pomegranate syrup, and with crushed pastry, and with walnuts. And you can just eat and say ‘C’est la vie!’ It tastes wonderful. So many flavours. Spicy and sweet. It’s called muhammara.”

“Kebab—we have six or seven different kinds of kebab… one with onion, one without. One is so spicy. One is with tomatoes…”

“People, when they go to restaurants, they stay there for like four or five hours. Yes! They should enjoy the table. First they will have their coffee. Then they will have the appetizers. And then the main dish will come.Then they will have the sweets. Then the fruits, with nargila [water pipe]. Then they will have a last coffee and tea. But they will sit there, and they will enjoy it. People sit and enjoy the table.”

Preserving the Future

“A lot of our old people, they won’t eat anything that is made in factories.”

Azad’s wife brings to the table a saucer spread thin with a deep red, seedy paste which looks a lot like harissa [a chili pepper paste] to me. It’s drizzled with olive oil, served with flatbread and often eaten with cheese. Homemade in summer, jarred with olive oil and salt, it will last for up to 2 years. It’s one of the most flavourful things I’ve ever eaten.

“We always avoid [food in cans] when we can. My grandma, they used to dry tomatoes, and they used that in everything. In the dishes, in salads even. We make tomato paste, pepper paste…it tastes lovely. We make it at home. Until now, in Syria, they value things that are made at home.”

Just as Azad’s family preserves produce each summer to carry them into the future, they are intentional and careful to preserve their social way of life.

“A lot of habits come in a ‘package.’ They come with a special societal structure. Look at all the cultures that have rich cuisines—the social structure is their family, or tribe. Like the Italians. Because if you’re living alone, why on earth would you cook? And you won’t enjoy that. But when it’s your family, and somebody’s cooking, you will have great compliments from ten people for making something very delicious—so of course you’ll do that.”

“You know, we have a [saying]: ‘Heaven without people is hell.’ ”

Our conversation shifts to their friends from Syria who went to Europe to try to make a life. So many of them are desperately lonely. They are starving for the kinds of relationships that nourished them their whole lives. We talk about how different life is for them here in northern Iraq. On this dead-end street, where their house sits cheek-by-jowl next to their neighbours, they don’t get many visitors.

Even after years here, it’s just not like home.

It becomes crystal clear that Azad and other Syrians who fled home because of war lost so much more than a house. They lost more than 2,000 year-old bazaars. They lost their very pattern of life—a way of being that fed them in every way imaginable.

It seems likely that the way back home, whether in Syria or somewhere else, will begin around the dining table.

“Nobody drinks the coffee alone. We don’t do things alone. I really love it. It’s like a magical thing.”

Kibbeh

For the kibbeh shells:

For the kibbeh shells:

1 lb finely ground beef or lamb

1 medium onion, minced

1 and 1/2 cups medium bulgur (cracked wheat)

1 tsp salt

1/2 cup walnuts or pine nuts, chopped

For the meat filling:

1 lb finely ground beef or lamb

1 medium onion, finely chopped

1 tsp allspice

1/4 tsp cumin

1 tsp ground coriander

½ tsp ground cinnamon

1 tsp black pepper

½ cup sour pomegranate seeds

Vegetable oil for frying

To make the shell:

Soak bulgur for 15-30 minutes in cold water. Drain. Place in the center of a clean tea towel, gather the ends securely and squeeze the bulgur to remove excess water.

Place 1 lb. ground meat, 1 minced onion, and 1 tsp salt in a food processor and pulse until it is finely ground, almost into a paste.

In a large bowl, combine the meat, bulgur, and nuts and mix with your hands until the mixture has the consistency of dough. If needed, add a cold water, a little bit at a time. Chill mixture in the fridge while you cook the filling.

To make the filling:

Saute the remaining onion in olive oil. Add the ground meat and spices. Cook until lightly brown, breaking up the meat as you stir. Remove from heat. Allow to cool for 15 minutes. Gently fold in pomegranate seeds.

To assemble the kibbeh:

With wet hands, form egg-sized balls of the shell mixture into balls. Plunge your thumb into each ball, rotating and pinching the edges to make something of a cup shape. Add filling, pinch closed, and quickly form the ends into the shape of a football. You don’t want too much dough at the ends, nor do you want the walls too thick or thin. It’s not complicated, but will take a little practice.

Chill for one hour before frying.

Fry in oil until golden brown on all sides. With a slotted spoon or tongs, carefully remove the kibbeh and place them on a pan lined with paper towel to drain.

Serve with tahini sauce, tzatziki sauce, or plain greek yogurt.

Should make 25, give or take.

Chapter 2: Post-War Food in Syria

When war broke out, it changed nearly everything… including the food people ate, and how they ate it.

It’s essential for traumatized people to establish rhythms of normalcy, and food is one of the most essential rhythms there is.

I’ll admit, some of the best meals I’ve ever had were made by refugees in tents, all of us sitting around a plastic mat chowing down on chicken, beans, okra, rice, and all kinds of other local dishes like kofta, kuba, dolma, and more.

When you really think about what people can make out of the small, simple portions of food they receive, it’s downright astounding.

One of the best of these meals I ever had was in the tent of my friend, Hasan. Hasan and I have traveled in Syria and Iraq together—visiting families, delivering aid, and enjoying unexpectedly delicious meals all over the place, but nothing beat the meal his family laid out for us in the camp where they live.

Recently I caught up with Hasan, who received refugee status and is now studying nursing in the United States, to learn more about that amazing meal and how food typically works in displacement camps across Iraq and Syria.

“Well, each camp or community is different,” he says, “but most of the time there’s a card system. Each family has a food ration card listing how many people are in their family, and they take that card each month to receive food from NGOs or the government.”

He also explained the practicality of the food they receive: “They usually give out dry food like rice, beans, sugar, flour, oil, and things like this once a month. That food lasts longer and is cheap.”

The food is also heavier in starches and carbohydrates, making it a cheap way to keep people alive.

The problem is, camp food rarely provides much in the way of vitamins, minerals, or good fats. To enjoy food like meat or even eggs is considered a luxury in many camps, and families typically have to find work outside the camp to be able to afford that kind of protein.

That’s probably why one of our first projects with Hasan and his team was to provide egg-laying chickens to communities in Hasan’s homeland. Displaced and war-torn families are desperate for good protein!

So what about food preparation?

Again, Hasan explained it depends on the camp, but generally each family is responsible for creating their own space for cooking.

“Each family has a small one-meter-by-one-meter cinder block space near their tent that’s used as a kitchen. Each of these spaces has a small stove… Usually there isn’t electricity, so they use gasoline or propane stoves most often.”

It’s essential for traumatized people to establish rhythms of normalcy, and food is one of the most essential rhythms there is.

Hasan then explained how camps just a couple of years ago were providing multiple rations of food per month, but now, much of the money is drying up and refugees are left with fewer options. Some families send their children out to beg, or their sons to look for work or to try crossing into Europe. But most just wait, glad to be out of harm’s way but eager for things to get better, whether that means returning home or starting something new in another country.

In Syria, families have been waiting for things to get better far too long. After years of siege and conflict, tens of thousands of starving families are showing up in shelters and camps with extremely malnourished children. Fortunately, you’re providing hot meals for them until they can get back on their feet. Just this year, you’ve served over two million meals in Syria.

Like the camps in Iraq, shelters and kitchens in Syria provide the most cost-effective, filling ingredients they can. Rice, lentils, pasta, and other hearty starches make up most of the meal while onions and other root vegetables add some flavor and nutrition.

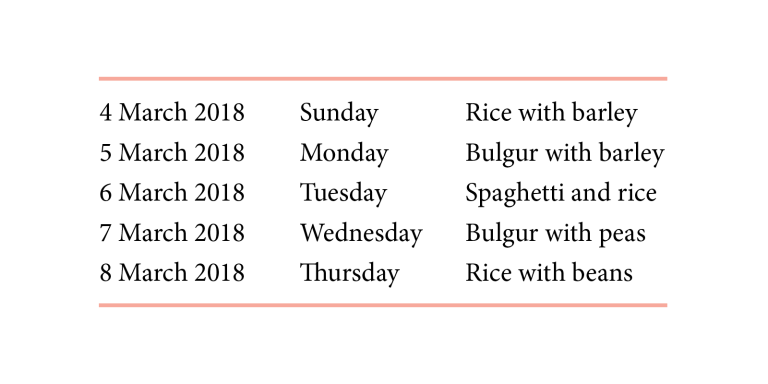

Here’s the menu from a recent week at our emergency kitchen in Deir ez-Zor:

While these meals are a far cry from what these families may have eaten before the war, they are grateful for the nourishment.

Here’s is a recipe for one of the dishes that is frequently served through our hot kitchens in Syria:

Mujadara

1 cup green or brown lentils

4 cups water, divided

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 large yellow onions, diced

1 tsp salt

1 cup white rice, soaked in water for 10-15 minutes, then drained

Black pepper

Fresh parsley for garnish

For the crispy onion topping:

Vegetable oil

1 large yellow onion, thinly sliced

Instructions:

In a small saucepan, bring the lentils and 2 cups of the water to a boil over high heat and then reduce the heat. Cover and simmer until the lentils are par-boiled (10-12 minutes). Remove the lentils from the heat, drain, and set aside.

Heat the oil over medium-high heat in a large skillet with a lid. Cook the onions for about 40 minutes until they are deep golden brown—darker than regular caramelized onions. Sprinkle salt on the onions while they cook.

Carefully pour the remaining 2 cups of water in with the onions and turn the heat to high. Bring the water to a boil, then reduce the heat to low and simmer for 2 minutes. Stir the rice and par-cooked lentils into the onion mixture. Cover and bring back to a boil. Add the salt salt and pepper and reduce the heat to low. Cover and cook for about 20 minutes or until the rice and lentils are cooked through and all the the liquid has been absorbed. Remove from heat and add more salt and pepper to taste. Finish the Mujadara with a drizzle of olive oil and garnish with fresh parsley.

For the crispy onions, heat the vegetable oil in a small pot over medium-high heat (to 375 degrees F). The oil is ready when you add a piece of onion and it bubbles rapidly. In small batches, fry the onions until they are crispy and golden brown. Carefully transfer to a paper towel-lined plate to drain, and then sprinkle on top of the Mujadara.

Chapter 3: You’re Invited

Of all the things that bring us together as humans, is there anything more unifying than food?

Every day, every person alive thinks about it.

Whether it’s a three-star chef buying ingredients at the market, a farmer harvesting her crop, an astronaut opening a packet of freeze-dried food on the space station, a businessman on his lunch break, or refugees elbowing their way to a truck full of rice—all of us, everywhere, think about food.

One thing we love about you, though, is that you don’t just think about food for yourself and your family—you also think about food for others in need.

You’ve proven that by sending millions of tons of food to fleeing families in conflict zones across this region and by providing more than two million hot meals in Syria in 2018 alone.

You’ve shown immense compassion for refugees and displaced people, and we’re grateful.

Many of you have asked what else you can do to stand with and support refugee families around the world, so in honor of World Refugee Day on June 20, we thought we’d provide some practical ideas for how to engage with refugees.

The goal of this experience is not primarily to raise money, but to dive beyond compassion into the depths of empathy. We want you to stand in their shoes, to sense the fullness of their humanity, and begin to feel how connected we really are.

Azad, Sheraz, and Hassan… they are not just numbers, and they are a whole lot more than their status as “refugees.”

They are people like you and me. Maybe they love to cook for their families and hate doing dishes. Maybe they have one dish their grandma makes that they just can’t stop eating. Maybe they’ve got a favorite kind of tea, a weakness for baklava, or a food they hate that everyone else loves.

On June 20, we invite you dive in deep with these friends by hosting a dinner party in honor of World Refugee Day. It’s the perfect way to learn about Syrian culture, celebrate the lives refugees beyond their refugee status, and recognize the impact that displacement has had on their everyday existence.

Here’s how to make it a success:

1. Use our free, beautifully designed dinner invitations to invite your neighbors, your small group, your extended family, or your coworkers. The invites come in a printable or digital format… we’ve even got a version for you to use on your Instagram stories!

Download Invites and Recipe Cards

2. Use the recipes above to cook up some delicious Syrian food and get a taste of what families in Syria ate both before the war (kibbeh) and after (mujadara). For more menu ideas, take a look at these Syria food blogs:

3. If cooking isn’t your thing or these recipes are too daunting, feel free to serve a more simple Syrian-inspired dinner with hummus, pita, fresh veggies, olives, and grilled chicken or lamb.

4. Include your children, family, or friends in the cooking process and discuss what Syria was like before the war. (Did you know it was a booming tourist destination before the conflict began in 2011?)

5. Take a picture of you and your guests at dinner and let us know how it goes! Post it on social media with the hashtag #EatLikeSyria and tag us (@preemptivelove). Or, if you’re not on social media, email it to us and tell us how it went. It’s always super encouraging to our staff to see our beautiful community engaging with their refugee friends in creative ways.

If you want to take this idea to the next level, here are some ways you can do so:

1. Visit a Middle Eastern market if you have one in your area. Strike up a conversation with the people who run it, get some cooking tips, hear their story, and share your own.

2. If you’ve got a tablet or a laptop, pull up this resource and let people scroll through it. This one is especially fascinating for kids and there is nothing graphic or violent in it, though parents should still look through it to make sure it’s appropriate for their children.

3. Turn up the sounds of Syria with these Spotify playlists featuring Syrian artists:

4. Have a dinner and movie night and watch Human Flow, a documentary about the refugee crisis (available to watch on Amazon Prime.)

Stand in their shoes, sense the fullness of their humanity, and begin to feel how connected we really are.

5. Print out these articles and have them out on the table as conversation starters.

- Refugee Life is Hard. It’s Even Harder When You’re a Woman.

- The Radical Hospitality of Refugees

- 5 Questions About the Syrian Civil War You Were Too Embarrassed to Ask

- Syria: Finding Hope After 7 Mind-Numbing Years of War

- If You Were a Refugee, Wouldn’t You Deserve a Full, Stable Life, too?

6. You could play this video about how you’re showing up in Deir ez-Zor, or this video about a young Syrian refugee who is rebuilding her life with your help, and discuss the amazing work you’re making possible with refugees in Iraq and Syria.

7. If you feel so inspired, you could add up the cost of the meal and donate that amount to our work with refugees in Syria. Just $10 will provide 90 meals for displaced Syrian families on the frontlines of conflict.

- Empower your kids to give, too! Since just $5 provides 45 meals, our little ones can have a huge impact in Syria with just their chore money or the change they make from a lemonade stand.

8. After dinner, ask people to pull out their smartphones and look up organizations that work with refugees in your area. See if there is a way you can get involved with resettled families where you live.

Be creative! This list is not exhaustive… figure out how you can take a step toward your refugee friends on World Refugee Day.

As a bonus for making it to the end this piece, here’s a Syrian drink recipe to enjoy at your dinner party:

Syrian “Polo” Drink (Lemon and Mint)

1 ½ cup Fresh lemon juice

4 cup Water

½ cup Superfine sugar or simple syrup

1 cup Fresh Mint

1 tsp Orange blossom water (optional)

Pick the mint leaves, making sure to get rid of all the stalks. Add all ingredients to a blender and blend until the mint is finely ground.

Thank you for honoring our displaced friends on World Refugee Day. Thank you for sharing their stories and experiences. Your compassion is transforming their present reality. Your empathy will transform their future.

If you would like to go even further, and give to support refugees in Syria and Iraq as they rebuild their lives—or invite your friends to join you in supporting them—use the form below.

Photo credits:

Aleppo neighborhood, 2007. Photo by Thomas Stellmach / CC BY-NC 2.0.

Vegetables for sale in Aleppo, 2010. Photo by Bruno Vanbesien / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Kibbeh. Photo by Ron Dollete / CC BY-ND 2.0.

Restaurant in Aleppo, 2010. Photo by Alessandra Kocman / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Baskets of nuts for sale in Aleppo, 2006. Photo by Dan / CC BY-SA 2.0.