The car with cleaning supplies poking out of the rear windows squeaked into the high school carpool line.

Of course the brakes only squeak when other kids are watching. Juli jumped into the car and hoped her parents would drive away quickly.

Juliana moved to Tennessee from Colombia when she was three years old. Her parents worked all hours cleaning houses and doing odd jobs in order to send their two daughters to a Christian high school. Her mother’s work-induced back pain served as a physical reminder of how deeply she cared for her girls.

From as early as she could remember, Juli’s prayer was for papeles (papers)—a prayer that lingered in her mind constantly and brought continual anxiety.

Juli’s family is undocumented. From the outside, her parents live like their neighbors: paying taxes, providing for their kids, cooking delicious dinners (I can attest to how delicious they are).

The papeles—or lack of them—are the only difference between Juli and her neighbors.

High school was a proving ground for Juli’s identity. She told me how she kept her immigration status to herself and learned to tell people what they wanted to hear. Parents of friends would ask if she’d ever been back to visit Colombia. Even though there was no way for her to travel internationally, she’d give them the answer they expected. “Yes! I just spent time with family and ate arepas!”

Friends would ask why she didn’t have her driver’s license yet, and she’d reply that she was afraid to drive. Spanish teachers would defer to her on what Colombia was like in class, not knowing she was undocumented and hadn’t been to Colombia since she was three.

One particular day, Juli was set to speak in front of the student body. “What are the odds? Juli is speaking on Cinco de Mayo!” said the announcer…

There were times when her lack of papeles weighed heavier than being asked about her driver’s license. She wished to have the freedom to come and go from America. Juli’s grandmother in Colombia has dementia, and she’s unable to be with her. She feels trapped in her living room, powerless to help her grandmother.

More often than not, Juli says she found herself wishing for white skin— for the privileges and ease of life it granted her white friends. She would imagine going to school without squeaky brakes, not having to answer so many questions, and generally fitting in at her mostly-white school.

Now that she’s a junior in college, Juli takes more pride in her identity. Growing up, she felt caught between two cultures: that of her Colombian parents and her American upbringing. So when a mentor explained that she was “third culture” and had the freedom to choose aspects of both her Colombian and American heritage, she came to love the unique and beautiful combination she could build.

“Maybe I don’t look it or don’t have proof of being American, but I feel it.” She turned this concept into her college essay.

Maybe I don’t look it or don’t have proof of being American, but I feel it.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was introduced the year Juli turned 17. It enabled children of undocumented immigrants to become eligible for work permits and a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation. DACA is a resuscitation of the Dream Act, a bipartisan bill initially proposed in 2001 but never passed.

Juli and her mom spent two months gathering materials—receipts, paperwork, etc.—to prove she and her sister had been in the US every single month since elementary school. Imagine trying to find proof of where you lived and what you did every month for the last 15 years…

The process was time consuming and demanding, but ultimately rewarding. After paying the $495 fee ($410 for the application and $85 for the fingerprinting), Juli received her first U.S. issued identification.

Official forms may not seem like a big deal to many of us, but for people without documents, life can get complicated.

Juli jokes about two times in her life when she didn’t exist. The first was when she realized her Colombian passport had expired. “Mama, did you know I don’t exist anywhere?” The second was last year, when Juli re-applied to DACA and the government called to tell her they lost all her documents. (Don’t worry, they eventually found them…)

DACA recipients have to renew their status every two years and they still face major limitations. When it came to applying for college, Juli wasn’t eligible for in-state tuition at Tennessee state schools since she technically didn’t have in-state residency. She was ineligible for federal student aid, loans, and almost all scholarships, including ones set aside for international students. Though her grades and activities normally would have warranted sizeable merit checks for college, she had to limit her application pool. Lipscomb University was the only school that had a scholarship based solely on ACT scores and grades.

Now, three years after getting her first government-issued ID, Juli is striving to be an exemplary U.S. resident. She’s extending the thoughtful kindness and active listening that she didn’t personally experience in high school. She volunteers at a nearby women’s prison, acts as a Spanish translator for a local clinic, and is learning Arabic with some of her new refugee friends.

All the things she was denied she’s now intentionally pursuing: asking questions, caring to hear more, being gracious.

All the things she was denied she’s now intentionally pursuing: asking questions, caring to hear more, being gracious. Juli dreams of traveling the world and providing holistic healthcare to young mothers, survivors of rape, and women coming out of prostitution. Even at 21 years old, her life embodies an intentional choice to love anyway. She now has a rich community of friends from all kinds of backgrounds, cultures, and ages.

Chapter 2

Can one simple question really make a difference?

Does what we say and how we listen actually matter? In Juli’s case, the answer is a resounding yes.

Colombian by birth, American by upbringing, Juli got asked “why” questions a lot.

“Juli, why don’t you have your license yet?”

“Why aren’t you going on the international mission trip?”

So it only makes sense that the first time a friend honestly asked Juli, “What’s it like?” everything changed.

To Juli, it felt like no one cared to ask. High school isn’t always a place where people feel heard and nurtured by their friends. It’s one of our most formative experiences, but so often we leave scarred, hardened, and happy to be anywhere but.

One sunny afternoon during a trip to San Diego, Juli’s high school friend Savannah asked her a simple question. They had been chatting for a while about how their trip was going over lunch. From the outside, it looked like a normal Saturday meeting.

“What was it like for you to grow up being an immigrant?” Savannah asked, out of the blue.

This was the first time in her life that a friend wanted to hear her story.

Unable to control it, Juli began to cry. It was her senior year. She had gone to school with these people for four years. Yet this was the first time in her life that a friend wanted to hear her story. That feeling of being loved brought her to an emotional breakdown. Ever since being asked that question, she felt like she had a story worth sharing.

She grew in confidence in explaining her story. How she felt different, even at the age of three when her parents immigrated. How she felt American but couldn’t hide what she looked like. How she eventually came around to identifying as Colombian. She gained more pride in her different experiences instead of envying the sameness she noticed in high school. And most importantly, she learned how to ask questions of “the other” in her own circles.

Whose story is still waiting to be discovered, to be broken open? When we get to know people, we often don’t think to ask what school was like for them or what their childhood was like.

What if we were better at asking questions? Who would feel more loved?

As an important caveat: this isn’t a charge to demand life stories from strangers. Trust needs to be earned, not demanded. Rather, the question is how can we go deeper with the people we already know?

What if we were better at asking questions? Who would feel more loved?

It’s often a ripple effect. People are drawn to genuine people. When someone feels loved by your questions, more stories will come pouring in. Each person is a wealth of experiences. Maybe someone has always wanted to tell you their story but is just waiting for you to ask.

“Hey Savannah, remember when you changed my life?” Juli will jokingly bring up now.

Chapter 3

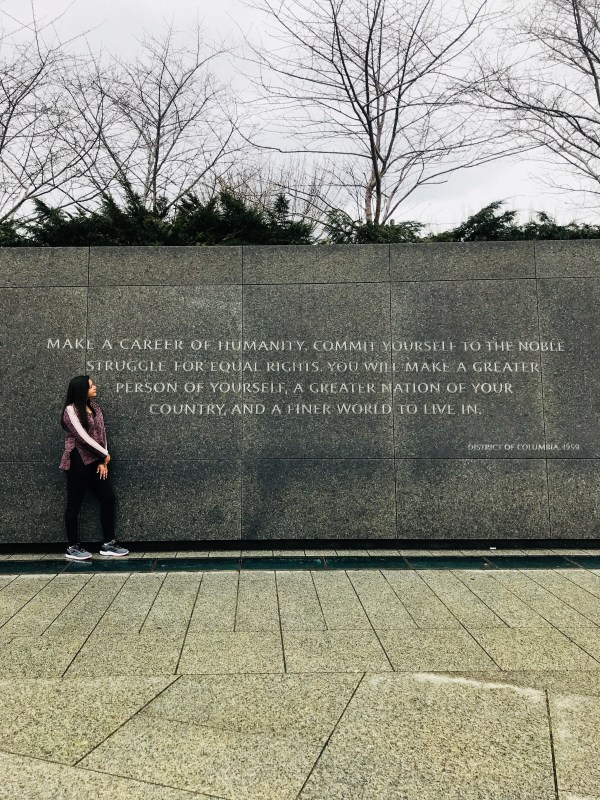

In 2018, Juli traveled to Washington, DC, with a group of Latino students to speak with legislators about their futures and the future of DACA.

For Juli and the other 800,000 DACA recipients, the two are inseparably linked.

The bill known as DACA was introduced in 2012. It protects children of immigrants from being deported, allows them to get work permits and driver’s licenses, but does not offer a path to citizenship. DACA recipients are often called “Dreamers” because of a similar bipartisan piece of legislation put forward in 2001 called The Dream Act. It didn’t pass, but the name stuck.

One night during their trip, Juli and seven other Dreamers stood on a stage in in front of 500 people. Each of the eight students held a candle, each one representing 100,000 DACA students. Tears streamed silently down Juli’s face as she thought about the people she was honoring—young people like herself with faces, favorite meals, and so much to offer.

Proof needed for DACA eligibility

During her trip to the U.S. capital, Juli and her friends scheduled a meeting with a representative from a district near Juli’s home in Tennessee. She’s known for her hardline stance on immigration, and Juli and her friends wanted to introduce themselves and explain how Congress’ decision would impact their lives.

The congresswoman had agreed to meet with them for 10 minutes. But as Juli and her friends waited in the foyer, their meeting time came and went. Eventually, a staffer came out to answer their questions in the hallway as the representative took her next meeting.

Juli was disappointed that she hadn’t had the chance to voice her thoughts and share her story. But she was proud that she’d found the courage to step foot in the office of a political leader who didn’t seem to want her around at all.

For DACA recipients like Juli, policy decisions about immigration aren’t political. They’re deeply personal.

For those of us who aren’t directly impacted, legislative controversy about deportation might be a controversial political battle we read about in the news and avoid talking about with our family. But it determines Juli’s future. It dictates her sense of personal safety, her wellbeing, access to healthcare, proximity to family, and career potential. It changes everything.

Juli was in the Senate chamber on February 15, when the Senate voted on a bipartisan immigration measure that would’ve offered a path to citizenship for 1.8 million undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children. It failed 52 to 47. Once again, Juli felt sad and frustrated.

Our policies have the power to make people feel welcome or unwelcome. Loved or unloved. Understood or misunderstood. Valued or devalued. Heard or ignored. Seen or unseen.

That trip had the potential to make Juli and her fellow DACA recipients feel all those things. Loved or unloved by our country’s government and Americans in general. Loved or unloved by us.

But regardless of how she is treated by others, Juli continues to live according to her values—extending to others what she is often denied. Whether it’s the inmates at the women’s prison where she volunteers, politicians who think she should be deported, or her refugee friends, Juli embodies the idea of preemptive love in every conversation, every relationship.

She is teaching me that choosing to love anyway is not about who “they” are. It’s about who we want to be.