The pavement is shiny and slick; light shimmers on the blacktop from the light pouring out of Haji Waad’s shop windows in Mosul’s historic Old City. It’s 4 a.m. and still inky dark outside.

It’s clear that Haji Waad has been awake for a while—since he got up to say morning prayers, at least. He stands in the narrow street, hose in hand, washing away dust and debris until the water in the gutter runs clear.

In every direction, you can still see the destruction and rubble left from the costly effort to liberate this city from ISIS. But this small part of the city, in the early morning hours, is quiet and clean.

There is no one else awake to see Haji Waad caring for the neighborhood like this. That’s not why he does it. Haji Waad loves the city of Mosul. This early morning ritual—between him, the city, and God—is an expression of that love. And this love unfurls far past his own block.

Customers begin to trickle in early—sleepy and still in pajamas, they come to the door of his shop. The clock on the back wall says that it’s 6:30 a.m., but it’s already so bright and hot outside, it feels much later.

Haji Waad dishes up fresh yogurt and clotted cream with purple ladles as customers come in. He counts out fresh, speckled eggs, and carefully places them in small plastic bags. Some neighbors stop in for milk, butter, and jam too. The yogurt and cream were sampled and chosen from a supplier earlier this morning, and delivered a short time ago. It’s already been a busy morning.

As neighbors return home carrying the makings of breakfast, it’s a fresh reminder that many of these families were able to move back after war because Haji Waad moved back first. His return had the same ripple effect as throwing a stone into a still pond, and the circles of positive impact continue radiating out in all directions.

When you ask how long Haji Waad’s family has lived in Mosul, you may as well ask how old the city itself is. They go back more generations than anyone has kept track. It was his presence in the neighborhood that gave others the courage to return. It was the fact that he reopened his business so quickly that provided others some of the practical things they needed to start over in a part of the city without many services.

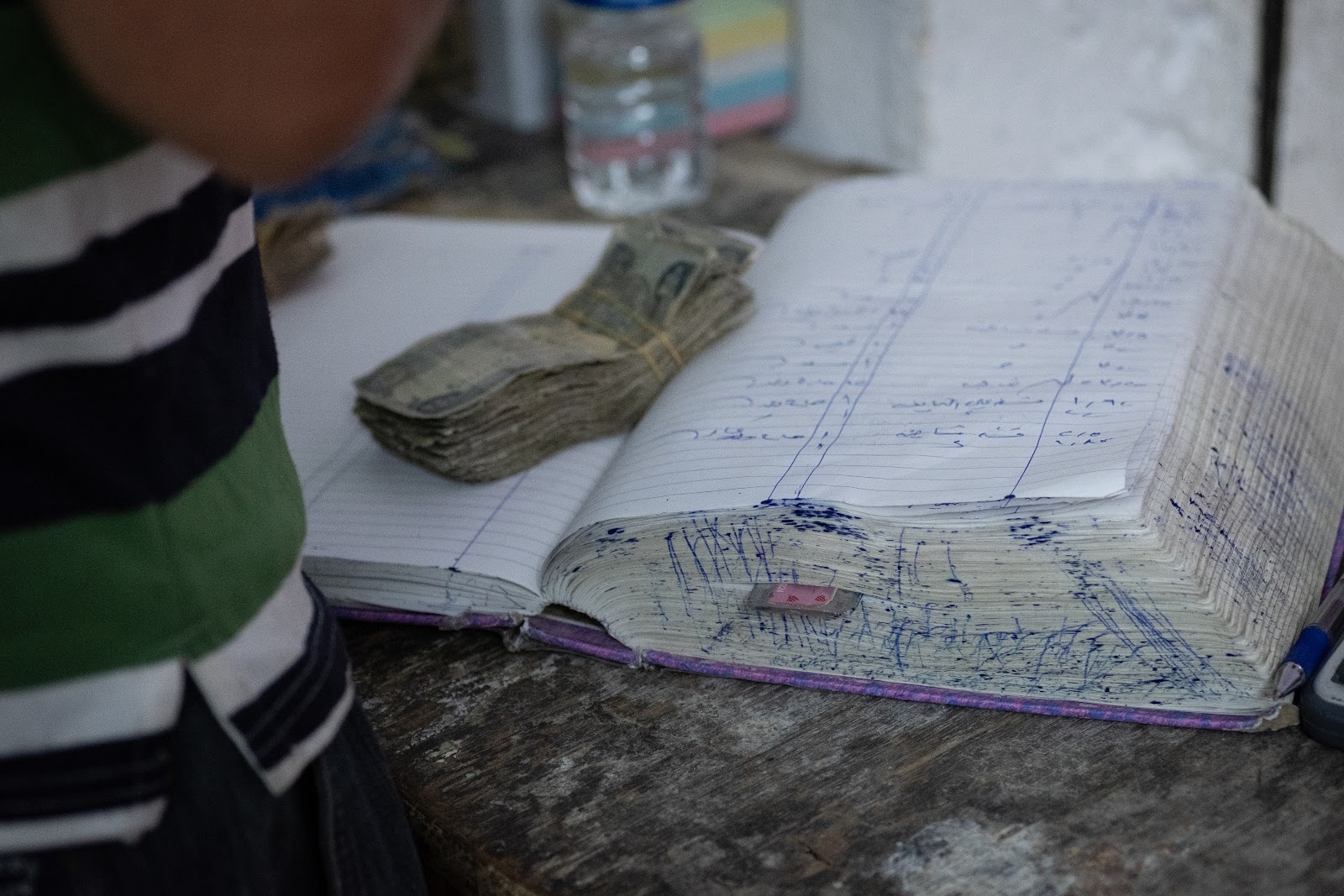

In purchasing inventory for his shop with cash, and not trying to negotiate credit, Haji Waad supported other business owners trying to rebuild their businesses too. His cash purchases gave his suppliers the money they needed for their expenses.

The farmers raising sheep and chickens outside the city, looking for shop owners to sell their yogurt and eggs, were able to buy feed for their animals and fuel to bring their products into the city. The baklava bakers were able to buy sugar, walnuts, and oil. Vendors selling more shelf-stable foods like jam were able to have a selection of stock on hand.

Together they form a vital circle of suppliers who all benefit from Haji Waad’s steady business, and who in turn, provide a benefit to their suppliers.

Haji Waad reopened his shop as soon as he could, and we were there to help, providing the funds he needed for inventory and supplies. As soon as there was a modest profit from the shop, he opened another business, a tea shop next door.

Tea is as essential to Iraqi culture as language. Tiny glasses of piping hot, sweet tea grace every possible gathering, and give an inexpensive pick-me-up throughout the day. Even more important than the tea itself is the social space that tea creates.

Opening this shop, with the familiar tinkling of tiny spoons stirring sugar into tea, was a call of welcome. It let the community know there was a safe place where they could gather again, where they could sit with each other, to talk. It pushed back haunting memories of fear and secrecy that were a core part of life under ISIS rule, and signaled a needed return to normal life. It also provided essential work for some of Haji Waad’s neighbors.

The demand for tea was brisk enough that one of the employees bought out the shop, moved it down the street a few doors, and expanded his wares to include the sale of his own custom loose tea blend to neighbors and other business owners.

Selling the tea shop allowed Haji Waad to open yet another business on the street—a sandwich shop that serves quick-to-eat meals from morning to afternoon. To order the “regular” is to get a diamond-shaped bun split and stuffed with ground meat, fresh tomato slices, and fried eggplant.

Even though most of the stores on the street are still empty and shuttered, there is a constant stream of traffic—construction workers going in and out of Old Mosul, dealing with rubble and reconstruction.

Now there was a convenient place for workers to get breakfast and lunch, and a tea shop nearby to wash it all down. There was a new business in the neighborhood that needed an employee. And the number of local suppliers who received regular orders grew too, as the sandwich shop helps to support a local baker, vegetable vendors, a butcher shop, and delivery men.

Providing Haji Waad with a small business grant directly supported dozens of other local businesses. It provided employment, which led to business ownership.

These are not temporary jobs. This is a lasting investment into a historic neighborhood, into families who have been here for countless generations, who want nothing more than to rebuild the beautiful city they love.

There is an ancient house up the street from Haji Waad’s shop that has been in the family for generations. Little of it still stands: the back wall, a single room, a portion of the staircase, and a bit of overhanging roof. It was lost to age and decay more than war. While the house is gone, for all intents and purposes, this remains an important spot in the neighborhood.

Each time the Islamic holiday of Eid comes around, the remaining family gather at their ancestors’ property to cook giant vats of soup on an open-air fire. They offer the nourishing soup for free to any in the neighborhood who come, whether hungry for nutrition or relationship.

They have always done this. As soon as they returned to Mosul, the neighborhood resumed the tradition, gathering together, sharing soup and stories.

When we show up in communities, this is what we get to be a part of, this is what we get to share with others. A love that ripples out over a broken community, rebuilding it a person, a business, a neighborhood at a time.

Give now and rebuild communities.