“We are not here advocating violence. The only weapon we have in our hands this evening is the weapon of protest. That’s all. And certainly, this is the glory of America, with all of its faults. This is the glory of our Democracy. If we were in a Communist nation we couldn’t do this. But the great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for our rights to be realized.”

– Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. sought to rescue America from a legacy of abusing its own citizens through segregation. With love in his heart and a commitment to nonviolence, he did what no war could do. He offered to return America’s humanity back to itself. He didn’t do so with only words; he did so with a limitless love. He died so America could come fully alive.

His faith gave him the vision of a Beloved Community where black children could hold hands with white children—a community characterized by unconditional love instead of poverty, racism, and violence. He knew this vision would cost him his life. He knew if he continued, his children would grow up orphans and his young wife widowed. He gave his life to free Americans from the cruelty of segregation that had seeped into our bone marrow, its DNA replicated in different forms of slavery since the Civil War era. It metastasized into Jim Crow laws, poll taxes, segregation, and lynchings. Racism rotted America’s soul, depriving us of the fullness of our own humanity.

King gave his life for our healing. If we believe in that healing, if we believe in unmaking violence, honoring his legacy should not be optional to us.

If we fail to commemorate that legacy, if we don’t take stock of the work still to be done, we’ll walk ourselves back into the poison of the very prejudice he sought to free us from.

Creeping prejudice won’t look like the segregation of the 1940s and 50s. It will take another, more shadowy form so we don’t recognize it right away. So we won’t root it out immediately. It will take the form of institutionalized injustice. Unarmed black bodies piling up in the street. It will look like Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, and Alton Sterling.

It will look a young African-American college student who was held at gunpoint and raped, sitting in a courtroom before a jury of 12 white adults who couldn’t convict her rapist after three days of deliberation—even though he never denied committing the act. I know because I was there, as a sexual assault nurse testifying to the wounds left on her body.

It will look like a particular kind of bias that sees people of color as somehow complicit in the crimes done against them. The dead can’t testify, but somehow they are assigned the blame for their own deaths—if only they’d followed orders, if only they hadn’t said or done the “wrong” thing. This violence terrifies African-American communities, instilling fear that their sons, their brothers, their husbands, or their fathers will be the next ones who don’t come home at night.

As Rodney Gainous Jr writes, “The perception of the black man in America is we cannot be trusted, we are violent, ignorant, aggressive, and criminals. There are countless stereotypes in our society; but this one ends lives of innocent individuals.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation illegal. But changing laws doesn’t change us or the values we hold. How do we honor the healing of our country that Martin Luther King died for? By accepting that the work is not done. And by taking on the work of rooting out our own indifference to the violence and injustice borne by people of color.

“The great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for our rights to be realized.”

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In one of his speeches (as recorded in the book A Call to Conscience), King called us to love more than our own justice and our own peace. “This call for the worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class and nation is, in reality, a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all mankind.”

Love is the only power strong enough to confront injustice.

Love is the only power strong enough to create a new story of healing.

Love asks, “Where does it hurt?” and moves toward the hurting.

What does this kind of love mean for us today?

- It means when we hear the protests of marginalized communities, we listen—even if we don’t agree or fully understand.

- It means if we have privilege, we stand beside our neighbors who don’t have privilege.

- It means if we have peace, we work for the person next to us who doesn’t yet have peace.

- It might mean we don’t protest for our own rights, but we work for our neighbors’ full rights and humanity to be recognized.

May we continue this work—and put this love into practice—today

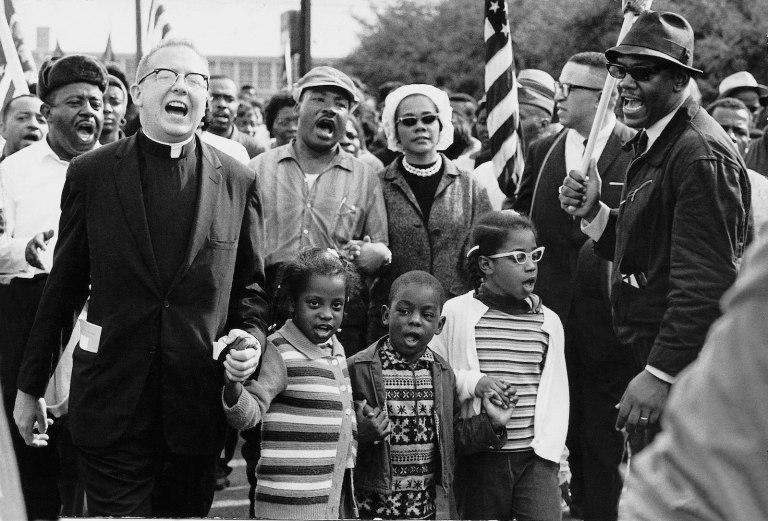

Featured image of Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at an interfaith civil rights rally in San Francisco, June 30, 1964 by George Conklin. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.