Eight years ago, we adopted a beautiful baby boy from Ethiopia. People often ask to hear our adoption story. And I always wonder… do you want my son’s birth story? Or do you want our now-story?

Do you want to know how he was a twinkle in our eyes before we held him in our arms on a Sunday afternoon in that impossibly hot, noisy orphanage in Ethiopia?

Or do you want to know how I wake up with fear clawing at my stomach every morning—fear that my beautiful brown son may not come home safe today? I’m terrified that the next story of a brown-skinned boy lying lifeless in the street will be about my son, because violence plays for keeps. I’m terrified that one day I will be forced to taste the same pain the mothers of Travyon Martin, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice have. I’m in agony of what we may share in common someday.

I don’t know how to walk this road.

My heart knows what my head refuses to admit: that I’m powerless to protect my son’s beautiful brown body from senseless acts of violence—from the systemic racism that stalks his every step.

He was called “n*gger” the first week of kindergarten. That was the day history broke in on me. The voice speaking this epithet was that of a 7-year-old child, but make no mistake: it wasn’t just his voice. An entire legacy of racism spoke through this little boy, right here in “post-racial America.” It was not his idea, not his own original hate.

History fed his disgust at my brown son’s existence. White supremacy fed his sense of entitlement to put my son “in his place.”

The quiet was eerie after the bus delivered my two sons home that day. Neither was eager to be the first to say what had happened. Shame followed them into our home that afternoon.

Finally, my older son, his voice shaking, repeated what had been said to his younger brother on the playground. My youngest hid away in his room. Why? I said to myself. Isn’t he too young to be wounded by the violence and hate that word carries?

We know that by age 7, ideas about race are firmly formed.

He did his best to duck and dodge, but he couldn’t escape the shame that was aimed right at his soul. That day, he was labeled less-than, a label he’d never had to wear before.

That was the day shame intruded into our home and sat down with us. Until then, being brown-skinned just meant “different.” Now brown carried shame. It meant that bigger people on the playground could divide and separate my son from his classmates. It meant he was all alone at school.

Brown now meant bad.

Don’t think these words leave a mark? Then why do 15 out of 21 brown-skinned children choose the white doll over the brown doll when given a choice?

The study I’m referring to was first conducted in the 1940s during segregation, then again in 2010 by documentary filmmaker Kiri Davis. “In Davis’ test, 15 of the 21 children said that the white doll was good and pretty and that the black doll, bad.”

Davis concluded that prejudice and discrimination had caused black children to develop a sense of inferiority. She said the children in her study did not hesitate when asked to choose. “It was just, boom, which is the good doll? They said because the white one is the good one, the black one is the bad one. They internalize these stereotypes that are out there.”

“People don’t realize at such a young age these children really get it,” Davis said. “Many [parents] didn’t want to believe that’s what’s still going on.”

We know that by age 7, ideas about race are firmly formed.

My heart beat itself bloody the day my youngest came home from kindergarten. Fear seeped into the marrow of my mothering. The hand that rested on my son’s shoulder lacked the unconscious affection it usually carried. I could feel my protective instincts kicking in, silently challenging anyone to demean my son again. I wished my hand on his shoulder could protect him from the experience of being viewed as a criminal (or a soon-to-be one) or treated as a second-class citizen.

I can’t protect him from that. And that is what tears at my soul—not being able to shield his soul from the relentless chant of racism. Our lives are shaped by its rhythms but those of us who are white don’t notice because it doesn’t affect us. You don’t recognize the song unless generations of your family has been terrorized by it. Detecting the beat of racism is a survival skill handed down in marginalized communities.

As I stood there with my son, without even realizing it, my soul resurrected my old soldier skills from my days as an Iraq War vet.

Planning ahead about who we would allow ourselves to be around…

Deciding not to let my son go into a gas station bathroom by himself…

Taking the nerf gun out of his hands while he played in our own yard…

Telling him to take the hoodie off his head—because today it’s just a Superman hoodie, but a few years from now it could endanger his life…

Panicking when a police car stops in front of our house while my son’s across the street from me because I’m afraid that 100 feet may be too far away for me to protect him.

How in the world could I spare my son from wondering, What’s wrong with me? Why did they talk to me like that? Why does my brother get teased for having a black brother?

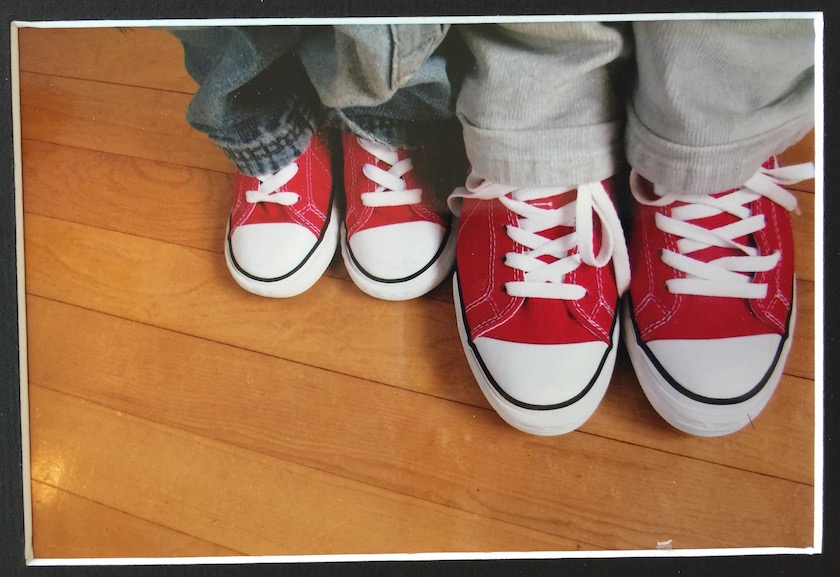

My son is a masterpiece. His laughter, his artist’s eye, that grin that cracks every stern moment. The greatest gift I could share with the world is all of him.

But now, instead of sharing him with the world around me, I have to protect him from the world.

Our adoption story? It goes like this…

His eyes found mine over the ten other crying babies, stacked orphanage style, three cribs high. His hand touched my face followed by his eyes. He was home. I was home. Cradling him in my arms for the first time was cotton candy and moonbeams.

Pure magic. Our adoption story is beautiful, isn’t it?

But what about my son’s life story?

I’m not going to stop saying Black Lives Matter because I’m committed to the rest of his life story.

My reality is that I can’t protect my own son. I can’t protect my son from the racism swirling all around him. But I can lift up his chin, look him in the eye, and say, I’m with you. No matter what.