When Sofia* picks up the food pack, she stumbles slightly, not expecting it to be so heavy. A smile spreads across her face. Her family of five, counting her tiny newborn, will have enough food this month, which isn’t always the case. In Venezuela, 91% of moms, dads, and kids live in poverty and one-third of the population–nine million people–don’t have enough to eat. This food pack distribution that our community of peacemakers makes possible is a lifeline for families like Sofia’s.

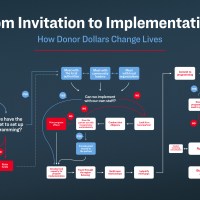

How unrestricted donor dollars become holistic programming can be a long and arduous journey. No two program implementations are exactly alike, especially since events such as presidential elections, war, famine, currency devaluation, hyperinflation, or a pandemic–all of which have happened in the places where we work–can stall relief efforts. However, there are a few constants. Using a food pack distribution program in Venezuela as an example, this is one example of how donor dollars become life-saving relief for those who need it most.

Phase 1 – Form Partnerships

We don’t arrive in a country and decide to hand out food. In fact, we don’t set up programming anywhere unless we have been invited in by someone who knows our work, or we have a chance encounter from which we foster a relationship. For example, a local partner with whom we implement relief programming in Colombia introduced us to an organization with operations in Venezuela. A serendipitous meeting with the husband of a friend of a friend put us in contact with the safehouse in southern Mexico, which we now support.

Relationships are the bedrock of our programming. We cultivate them by being physically present in the local context and by building trust through listening. We’ll meet with local government leaders, community leaders, local organizations, locals–anyone who has knowledge of the local community. Relationship building is an investment of time, but listening helps us identify the gaps in the community which the community wants filled. For example, in one of our projects in Colombia, a community was identified as being food insecure and lacking access to basic health care, but when we listened to community members, they told us they needed water more than food, so we implemented a project to improve access to potable water .

Once we have been invited to set up programming in a community, we evaluate if we can implement a program with our own staff. For example, we used an existing staff member to set up a sustainable farm in northern Iraq. We transferred one of our Syrian program officers to lead food programming in Lebanon. If we can’t implement a program with our staff, we look for a local partner or we could hire a local program officer. Local partners/program officers have the specialized knowledge of the surrounding context necessary for successful programming. Also, working with local partners/program officers builds up local capacity through job creation, knowledge sharing, skills building and expanded reach.

Once a local partner has been identified, we conduct due diligence to make sure the partner fits with Preemptive Love’s core values, especially regarding transparency and inclusivity. Not all potential partners work out. Sometimes, we have to part ways and return to the drawing board. Once a suitable partner is found, we fund projects by providing the partner with grant money, through which we develop the capacity for program implementation and reporting.

Leaning in and listening, building trust while forming relationships, and finding “the right” local partner/program officer can take months. This investment of time and resources is intrinsic to building holistic and sustainable programming.

Phase 2 – Build Program Infrastructure

After a local program officer is on board, either from our in-house staff, hired locally, or found through our local partners, we investigate what kind of relief is needed and where it is needed through building local relationships and listening. Listening helps us build trust in the local community. We are careful not to duplicate programming efforts that other organizations are already providing. We also look for opportunities that promote peace building.

Understanding the contextual dynamics is imperative for successful programming. If we provide food packs, we need to consider if the local community has ways to cook the food in the packs. Do they have the money to purchase the gas or electricity needed to prepare the food? How do we transport food if there is a gasoline shortage? Will families sell the food packs because they might need medicine or hygiene supplies more urgently? What kind of food should be offered? If a community is malnourished, the combination of proteins and carbohydrates in a food pack needs to be considered. How frequently should food be distributed? We don’t want to create unhelpful dependency. What should a project include to build capacity and sustainability in the community?

After committing to a program, we see if our local partner wants or has the capacity to take the program lead. If the local partner does not have the capacity, we hire a program officer if we have not already done so. Either our local partner, our program officer, or Preemptive Love international staff will gather and train local staff in preparation for setting up the program specifics. As our local staff listen to the surrounding community describe their needs, we may decide a program needs to pivot. For example, when we started working in southern Mexico, we thought we might introduce a jobs creation program but after an unexpected shift in Mexico’s immigration policies, we found that recently arrived migrants needed immediate food relief instead. If the program does not need to pivot, we finalize its set up.

Phase 3 – Program Implementation

In Venezuela, we committed to doing food distributions. With our local partners, we identified 6 vulnerable communities in which to work, providing food packs to every family in the community once per six weeks. We consulted with a nutritionist to decide what kind of food to provide, considering the levels of malnutrition, how much was needed to last a family of five for at least four weeks, and how best to distribute it. Next, we found local suppliers, thereby boosting the local economy, and had our team with the support of local volunteers distribute the food packs. After distribution, we performed a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) assessment to see if the food packs lasted for the required time. If there are problems in the distribution, the M&E phase provides an opportunity to find solutions to those problems or other concerns voiced by the community being served.

As in every phase of program implementation, listening to the local community is key. If the program needs to pivot, we rebuild the program infrastructure. If the program runs smoothly, we repeat the distribution process and look for ways to build sustainability when applicable. As we work in a region, we share skills and learning with grassroots non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to foster growth and resilience locally. In that way, we build capacity in places where we work.

*Not her real name