“Despite the abuses, after detention, many of us befriended and welcomed into our homes former US soldiers who guarded us. We’ve always believed there was another way.” –from an Open Letter to President Biden from Guantánamo

Trigger warning: this article discusses instances of torture.

779 men from 49 countries. Unlawfully detained. Denied due process. Beyond the reach of any US court. Waterboarded. Held in solitary confinement. Shackled in stress positions. Suspended naked from a ceiling beam for hours. Locked in a coffin for days. Given forced enemas. Sexually assaulted. Deprived of sleep. Deprived of food. Deprived of meaningful access to family or phone calls. Subjected to extreme cold. Subjected to extreme noise. Subjected to extreme pain. Tortured.

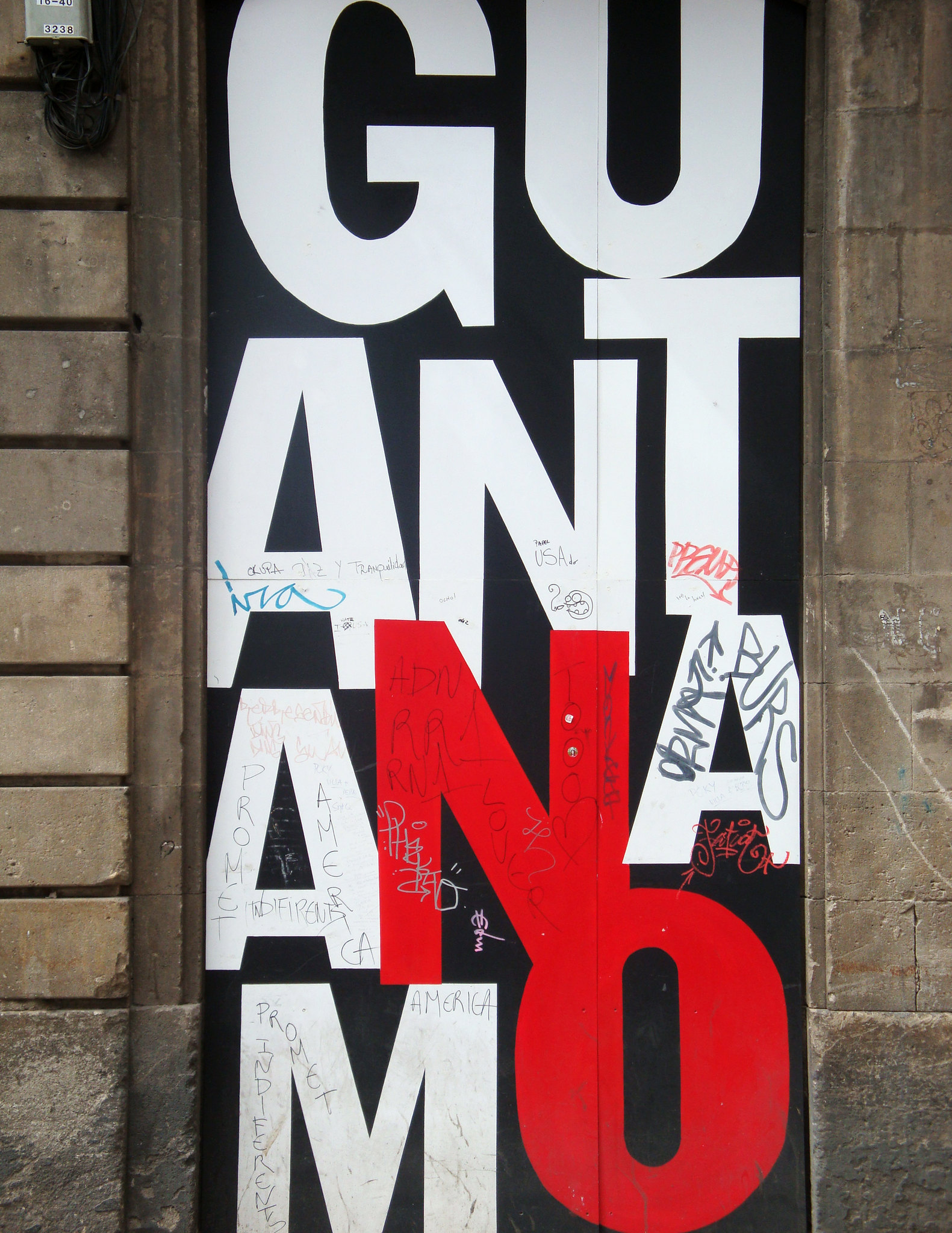

The Guantánamo Bay detention camp was opened to house “the worst of the worst” as the US fought the global war on terror. Guantánamo Bay’s infamy is its absence of human rights. The rule of law, which requires accountability, just law, open government, and accessible and impartial justice, does not exist in Guantánamo. Detained men have not been presumed innocent until proven guilty. Some have died under suspicious circumstances* unbelievably labeled as “suicides.” What the men detained at Guantánamo Bay experience is a side of the US that most US citizens do not acknowledge exists.

Many of the present and past Guantánamo detainees are thought to have been innocent. It is estimated that 86% were arrested by Pakistan or the Northern Alliance and sold to the US for $5,000 each after the US distributed flyers offering huge bounties for “suspicious people.” The detained men were farmers, taxi drivers, cobblers, and laborers caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. These captured men were locked up, without a trial, because after they were classified as enemy combatants, they were not allowed hearings or legal representation. For the fathers and sons held at Guantánamo, being denied basic human rights is their only experience in the United States. They have not known the US’s generosity, freedom, justice, or opportunity, aspects for which the war on terror was waged.

The war in Afghanistan officially ended with the US troop withdrawal and the transfer of power in Afghanistan from Ashraf Ghani’s government to the Taliban. Former Guantánamo Bay prisoners negotiated the US withdrawal and are presently serving as ministers in the Afghan government. Yet, the detention camp remains open at a cost of $540 million dollars per year, roughly $13 million dollars per prisoner.

There are 36 remaining prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, two of whom have been held since the detention camp first opened over 20 years ago. The imprisoned men fall into three categories: those who have been charged with war crimes in the military commissions system (a military court of law used to try law of war and other offenses), those held in indefinite law-of-war detention, and those held in law-of-war detention but are cleared for release. Law-of-war detention states detaining enemy combatants without charge is legal because it is preferable to killing them.

Twelve men have been charged with war crimes in the military commissions system. (Critics of the military commissions system have referred to it as a kangaroo court because the military commissions system allows for hearsay testimony. Also, defendants do not have the right to appeal, and the military acts as the defender, the judge and the jury.) Two men have been convicted while ten await trial. Five men are held in indefinite law-of-war detention, meaning “they are too innocent to charge but too dangerous to release.” Of the 19 men approved for release, some were approved over ten years ago. These nineteen men need to find countries willing to take them.

Many inmates who have been charged with war crimes under the military commissions system are stuck in the limbo of endless pre-trial hearings. One of the most debated issues of pre-trial hearings is whether torture evidence can be used in the trials. This use of torture to gather evidence bothers some interrogators too. Mr. X, a pseudonym for an interrogator of Guantánamo Bay prisoner Mohamedou Ould Slahi, said he needed to “strip away his humanity” as an interrogator. Mr. X’s job was to make Mohamedou talk using enhanced interrogation techniques, which Mr. X considers to be torture by his own standards. “When I was there, and we were told at one point that we were at this historical – this historical point in the American history, you know, that we were heroes and we were on the side of righteousness…But if you take the Slahi case alone…We’re not on the right side of history…People should never be treated that way. And that’s created a lot of problems for my psychologically…I had, basically, a mental collapse over it.” After Mr. X left Guantánamo, he started drinking, distanced himself from his family, and thought constantly about hurting himself.

What Mr. X describes is moral injury. The origin of moral injury comes from Homer’s war poem “The Iliad” by way of psychiatrist Jonathan Shay in his book Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. Shay sees “The Iliad” as a story about “the undoing of Achilles’ character when he sees his commander betray his sense of what is right.” Shay observed that seeing an authority person betray his ethics causes disillusionment and a desire to do bad things in the viewer, which was defined as moral injury. In 2009, a new group of researchers writing in the Journal of Clinical Psychology Review expanded the definition of moral injury to include the psychological, emotional, behavioral, social, and spiritual impacts of doing something, witnessing something, or failing to prevent an action that violates a person’s moral core. This definition holds space for both the individual’s betrayal of what is right or his observance of a betrayal by someone in a position of authority.

Society teaches us that being a good person means doing the right thing even when it is difficult. As a society, we tell ourselves there is a clear difference between right and wrong, and doing right will be rewarded while doing wrong will be punished. This belief system is called just world belief, and people are drawn to it because it gives them a sense of control when the world seems chaotic.

Just world belief is especially popular in the US, underlying many of its cultural beliefs, such as hard work leads to success, or success is due to merit. Just world belief underpins war culture. We see our troops as the good guys, or as Mr. X. put it, “the heroes…on the side of righteousness.” However, different rules apply during war, when doing the “right” thing sometimes means doing the wrong thing. For example, a soldier may be asked to be ready to kill a child in order to save his fellow soldiers, which was a potential circumstance in the Iraq War. This type of situation is called contingent conflict because making that decision carries a moral price.

The US society asks some people to serve in the military instead of making everyone serve. The men and women who serve get sent into conflict to keep all of society safe, and that conflict is rife with moral danger. If the people who serve, including intelligence analysts, drone operators, and the men and women throughout the military chain of command, act in a way that violates their ethics and suffer moral injury, their moral injury is the price they pay so that society can keep believing in a just world. That is why society needs to accept its share of the moral burden. It needs to recognize that war, the unlawful detention of people who are innocent until proven guilty, and torture lack moral certainty. Society is culpable in the moral injury that the people who serve carry. Perhaps the most urgent reason to close the Guantánamo Bay detention camp is to promote the healing of society’s moral injury and improve its moral health.

*In 2006, three prisoners who had just ended a hunger strike to protest their detention, allegedly killed themselves. The US Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCSI) maintains that these three prisoners, who were not in adjoining cells, almost simultaneously made a noose from torn sheets and T-shirts and tied it to the top of the eight-foot-high mesh wall. Then, each bound his hands, (one also bound his feet), stuffed more rags down his own throat, climbed up on a sink, put his head through a noose, tightened it, jumped off the sink, and hanged himself. Two of the three men had cloth masks over their mouths, some say to prevent them from spitting out the rags stuck down their throats. During unauthorized autopsies performed on the bodies, the neck organs, including the larynx, hyoid bone, and thyroid cartilage were removed. These organs could determine if death had occurred by hanging, strangulation, or choking.