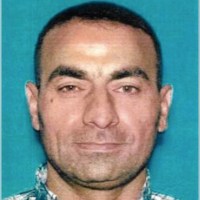

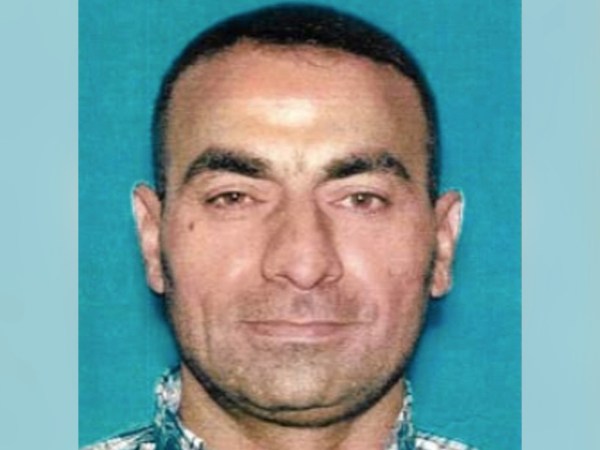

An Iraqi man who allegedly killed for ISIS managed to slip through the refugee screening process and resettle in the United States. Omar Ameen was arrested in California this month, accused of hiding years of terrorist activity in order to be admitted to the US.

His arrest raises questions about US refugee policy all over again. But maybe more importantly, it raises questions about ourselves.

First, the background—because, surprisingly, this story did not break through the chaotic 24/7 news cycle.

Who is suspected terrorist-turned-refugee Omar Ameen?

Ameen came from Rawah, Iraq, not far from the Syrian border. His accusers in Iraq say he was part of an al-Qaeda affiliate as far back as 2004, the early days of the insurgency against American troops.

He left Iraq for Turkey in 2012 and applied for refugee status, claiming to be a victim of violence. After more than two years of screening—first by the UN and then by the US State Department—he was approved to resettle in the States.

First, however, he allegedly returned to Iraq and took part in the murder of an Iraqi police officer, a day after ISIS captured his hometown. Ameen is accused of firing the fatal shot.

Five months later, he was on a plane headed for the US.

Initially Ameen settled in Utah, then California. The FBI, suspecting he had concealed his true identity, began investigating Ameen in 2016. There are no reports of criminal or violent activity while he was living in the US.

What does Ameen’s arrest mean for the refugee debate?

For most of his presidency, Donald Trump has argued that America needs “extreme vetting” precisely to stop terrorists from entering the country by posing as refugees—whether their intent is to escape their past (as may have been the case with Ameen) or to commit new acts of terror on American soil.

Refugee advocates, on the other hand, argue that the current vetting process is rigorous enough and the risk posed by refugees is small.

There’s some evidence to back this up. Studies show that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than those born in the US. Of the roughly 450 people who’ve been charged with terrorism (or killed in attempted acts of terror) since September 11, 2001, only 4 percent—19 people—were refugees or asylum seekers.

RELATED: 4 Things You Should Know About Refugees and Terrorism

Not one fatal terror attack has been carried out by anyone from any country included in any version of the president’s travel ban. Only three refugees have ever mounted a fatal attack—all of them from Cuba, all before 1980, when more stringent vetting procedures were put in place.

One failure of the refugee screening process does not significantly change this record.

And yet… one failure is all it takes to prove that our system for vetting refugees is not foolproof. It can be hacked. It can be exploited. It can fail, as it evidently did in the case of Omar Ameen.

But that’s just the point, isn’t it?

No matter how many walls are built, no matter how many countries are banned, no matter how much vetting is put into place—we can never guarantee absolute, unassailable security.

Safety is always, at best, a relative concept. We can take steps to minimize risk—whether it’s seatbelts in cars or more thorough vetting at the border. But we cannot eliminate risk altogether.

The question we must ask ourselves is: how much risk are we willing to live with?

How much risk will we accept for the sake of those who’ve endured more risk than we can imagine?

Security matters. There are entirely legitimate reasons to insist on careful, thorough screening for those coming to the United States, to insist on secure borders.

But it is possible to cling to our life and our perceived sense of safety so tightly that we suffocate all the joy out of life.

As a team serving refugees on the frontlines of conflict in Syria and Iraq, some of our most life-giving, joy-filled moments have come when we put ourselves at risk for the sake of those on the frontlines, when we step across the lines that separate us from those we fear, misunderstand, or marginalize.

To us, that risk is worth it if we can reach people, love them, and meet their needs.

Loving refugees is not a risk-free enterprise. The story of Omar Ameen proves that. But love itself is not a risk-free enterprise.

So let’s continue to show up for refugees—both in our communities and around the world. For those who cannot cross our borders, we will continue to meet them where they are and give them what they need to survive, recover, and flourish in their homelands.

The world is scary as hell. Love anyway.