Shepherding a caravan of two wives, eight children, and a few old women through ISIS-controlled territory, on foot, would make anyone grow up fast. Doing it when you’re only 17 and have just discovered your brother’s one and half-year-old son is missing would put years on anyone.

As the Syrian civil war intensified, Ahmed’s brother Farhan went ahead to Lebanon to secure a tent for the family to live in. Then, ISIS took control of their home city, Deir ez-Zour, and the family had to leave. Too young to be drafted and the only male in their caravan, Ahmed stepped into the role of “father” while the caravan was escaping. “It was weird, “ Ahmed remembers, “It forced me to grow up really quickly.”

Led by smugglers, the family walked for 20 days, moving mostly at night, through ISIS territory. Their smugglers were armed, and they constantly changed along the route. Ahmed struggled to find words for the experience. “It was frightening and stressful. It was a lot of responsibility for me. I can’t explain the feeling. I was always worried about one of the kids getting hurt.”

Checkpoints presented new challenges. Some they could pass through; others they had to avoid or bribe the guards. “Sometimes, fighting would break out between the army and the rebels, and we would have to turn around, wait, and try to cross again.” The kids were terrified and crying. Ahmed knew he had to keep the kids quiet, so he told them the truth. “We have to be quiet or else they’ll find us and we might get killed.”The eldest child was only nine years old. Looking back, he feels it was wrong to tell them the truth, but “it was the situation.”

And then, every parent’s worst nightmare came true.

Ahmed and the caravan were crossing the mountains from Syria into Lebanon. It was cold and dark, and they were exhausted. Terrified they would be caught, Ahmed was so stressed he didn’t “have my wits.” After about an hour and a half of walking, the group stopped to rest, and Ahmed did a head count. Mohammed, one and half years old, was missing. “I was terrified and lost and didn’t know where to start looking,” Ahmed recalls.

Ahmed grabbed two of their smugglers, and unsure which direction Mohammed had gone, ran, retracing their steps. After two hours, “feeling on the verge of giving up,” Ahmed found Mohammed near the bottom of the mountain, fast asleep in the nighttime cold. He had crawled away from the others, curling up to sleep, as the caravan began climbing. Ahmed had a “beautiful feeling of relief when we found him.”

After seven years in the settlement camp where we deliver much-needed monthly food baskets to hungry families, Ahmed is no longer the stressed seventeen-year-old who led a small group of women and children to safety. He is a father now; his own one-year-old son, a mini-Ahmed. “We look like each other, act the same, and have the same taste in food.” Ahmed is confident as a father because he learned so much about parenting by being around his brother Farhan’s kids, whom he feels are his kids too. He had a great father role model in Farhan, who raised Ahmed after their father died when Ahmed was only four years old.

He tells me being a father is difficult, but a great feeling. Nothing compares to the love he feels for his son and Farhan’s brood. “Nothing is more beautiful than to raise them by your own hand.”

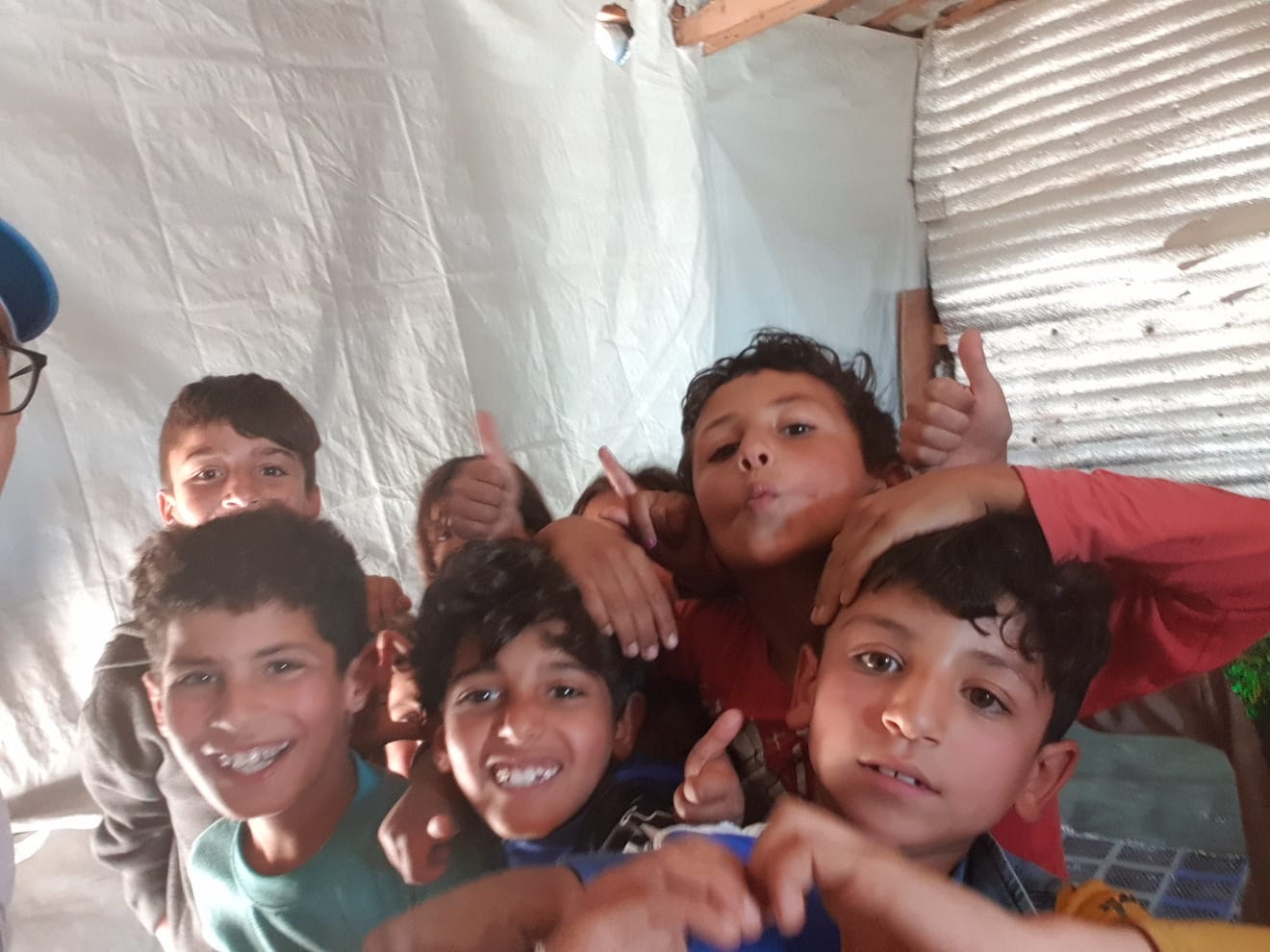

Ahmed’s hand is not as strict as Farhan’s, who stands in the doorway of the settlement school where we provide a daily hot meal to kids so they can learn to read and write instead of begging or working as day laborers. Because Farhan values education, he patrols the school entrance to make sure his kids stay in the classroom. This strictness is new for him, fitting him like a pair of too-tight shoes. Back home, in Syria, he was soft on his children, but here, displaced to a settlement camp in Lebanon, he can’t afford to be. Like any father, he worries his children will pick up bad habits if left unsupervised. Without gardens or parks, or the opportunity to move freely outside the camp, there is little for their children to do.

Farhan’s family, his two wives, their 12 children, Ahmed, Ahmed’s wife, and their son share a four-room tent made of wooden beams and plastic sheeting. There are no windows. The tent steams like a sauna in summer and freezes like an icebox in winter. The rooms lack furniture, not even a chair to sit on. The family sleeps on thin mattresses or carpets on the tent floor. If there is electricity, the kids watch TV when they are not in school. When the electricity is out, they invent dangerous games. Since the children do not have toys, they have to invent those too. One of their newest is shooting nails at one another using a rubber band, giving Farhan another task. In addition to patrolling the school doorway, Farhan is the Shutter-Down of Dangerous Games.

Farhan isn’t used to living with his family. Before they were displaced, Farhan worked as a day laborer in Lebanon, sending money back to his family in Deir ez-Zour, Syria. He saw his children only sporadically. Living together in one tent has made him much closer to his children, but it is a much different experience from his prior life. Obviously, it’s noisier. “We are always in each other’s faces,” Farhan says, but there’s something else: He used to be more mentally relaxed because he knew his family was living comfortably in Syria. Now, he feels ashamed of how his family lives, that he cannot give his children what they want.

“I have become a worse father because I am always angry and screaming,” Farhan, whose name means happy, confesses. The crowdedness of the settlement gets to Ahmed too. “I don’t have the room to say words to my own children.” Both fathers worry about their children’s future, especially if they stay in the settlement camp. When the kids ask when they are returning to Syria, both men can answer only with “I hope.”

Although dangerous and unstable, Syria is a siren song, calling them home.

*Special thanks to our Lebanon team’s program officer Sammy Ganama for facilitating this interview by organizing the meeting and translating our questions and answers.