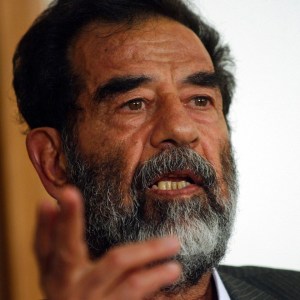

Saddam Hussein is making a comeback in Iraq. On Iraqi social media, at least.

Despite the fact that the former Iraqi leader was executed in 2006, Hussein’s deeds and words are being used in the online battle of opinions over the Iraqi Kurdish independence referendum.

On September 25, residents of the semiautonomous northern region of Iraqi Kurdistan voted on whether they should secede from the rest of Iraq. The outcome was hardly surprising: statehood is a long-held dream for Iraq’s Kurds and other Kurds elsewhere. Around 92% of voters said they wanted Iraqi Kurdistan to secede.

The reaction was also hardly surprising: Baghdad had said the referendum should not take place. After it did, they began to impose various restrictions on the northern region.

No matter the politics behind the referendum, it was a massively emotional issue for locals. In Iraqi Kurdistan, voters celebrated and remonstrated with those who did not vote. In Iraq, the opposite happened: many locals were upset and angry at their Kurdish neighbors. That’s when Saddam Hussein began to pop up again on social media.

“Social media is playing a role in fueling hatred between Iraqis.”

“Breaking news,” one sarcastic poster wrote on Facebook. “Saddam Hussein will address the Iraqi people this evening, about the Kurdish referendum on independence. Watch out for it!”

Some posted videos and news clips as well as pictures from Saddam Hussein’s regime, using the same rhetoric that deposed leader once used against the Kurds.

One Facebook page, for instance, posted a video of Saddam Hussein dating back to the 1970s, talking about how he rejected the idea of Kurdish independence. Other Facebook pages showed videos of speeches from the 1990s, during which Hussein attacked Kurdish politicians, as well as news reels of his visits to the Kurdish area in the 1980s.

Iraqi Kurdish social media also harked back to Hussein’s time—but from the other end of the spectrum, posting pictures of Kurdish locals fleeing into the hills, under attack from Hussein’s military.

There were also popular songs posted from before 2003, including one Kurdish tune that actually praised Saddam Hussein. Opponents of the independence referendum promoted this particular song.

While he was in power, Hussein treated the country’s Kurds abominably. The Anfal military campaign he oversaw in the 1980s aimed to get rid of the Kurds in Iraq; it is recognized as an act of genocide by several countries. The use of chemical weapons in Halabja in 1988 resulted in thousands of civilian deaths.

The Arabs and Kurds of Iraq who lived through these terrible events remember them. However, it seems that many younger Iraqis, either born after the Anfal campaign or after Saddam Hussein was removed from power in 2003, are ignoring it.

“It’s somewhat ironic,” says Irada al-Jibouri, a media professor at Baghdad University, “because most users of social networking sites [such as Facebook] who are either praising or cursing Saddam Hussein did not live under his regime. These young people are driven by certain ideologies or by religious beliefs that have more to do with emotion than logic.”

The mere mention of Saddam Hussein is usually enough to start a round of insults, arguments and recriminations on Facebook. It’s no different with Kurds and Arabs trading barbs online. And politicians use those emotions, al-Jibouri assert, because there is a belief that to distract the public from other issues, one should create a “permanent enemy.”

Al-Jibouri also believes there are “digital armies” who are trained to create disturbing content on sites like Facebook, to try and manipulate public opinion.

“Social media is playing a role in fueling hatred between Iraqis, and often it is due to ignorance,” said Samir al-Shaykhli, a local sociologist. “Iraqis online are not searching for the truth. They are searching for anything that will support their own views and biases.”

This post originally appeared on Niqash. Republished with permission.