You’ve probably seen the pictures of gray smoke plumes funneling up from Khartourm’s charred cityscape. You might have Googled “Sudan’s Conflict” and decided this is a civil war that doesn’t affect you, or thought, “A lot of innocent people are going to suffer,” as you hugged your kids close. Perhaps you gave up reading your internet search results because Sudan’s conflict is complicated, and you’re more concerned about gun violence or immigration issues at home.

Conflict dynamics–the causes of conflict, the intensifiers or spreaders of conflict, and the disruptors of conflict–intertwine with development gains in a “chicken-and-the-egg” causality dilemma. It’s hard to say which comes first: violent conflict or the erosion of living standards. After all, the popular uprisings which helped depose Sudan’s thirty-year leader President Omar al-Bashir began as protests about deteriorating living conditions, especially the soaring price of bread and fuel.

Violent conflict costs the world more than 14.4 trillion dollars a year. It fuels migration when people, such as Ukrainians, Syrians, and Afghans, flee war or gang violence, as did countless Haitians, Hondurans, Mexicans, and Salvadorans. Research shows that investment in peacebuilding brings prosperity, lowers inflation, and creates jobs. That’s one reason we’re so invigorated by our recent merger with Search for Common Ground, the largest dedicated peacebuilding organization in the world. Intrinsic to their Common Ground Approach is bringing different sides together to find solutions to benefit everyone. Search for Common Ground has been working in Sudan since 2009.

Search for Common Ground’s Work in Sudan

Search’s work connects marginalized groups, especially women and young people, to traditional authorities and institutions making and implementing societal decisions. By including women, young people, and different ethnic groups’ voices in conflict resolution activities, policies serve women and girls as well as men and boys and build bridges across ethnic dividing lines. By including all voices in decision-making, challenges such as access to water and grazing land have been met in a more equitable, lasting way. When they contribute to conflict resolution processes, participants gain agency, which deepens their resolve to keep peace. Here is one example of Search’s work empowering marginalized communities to become their own advocates.

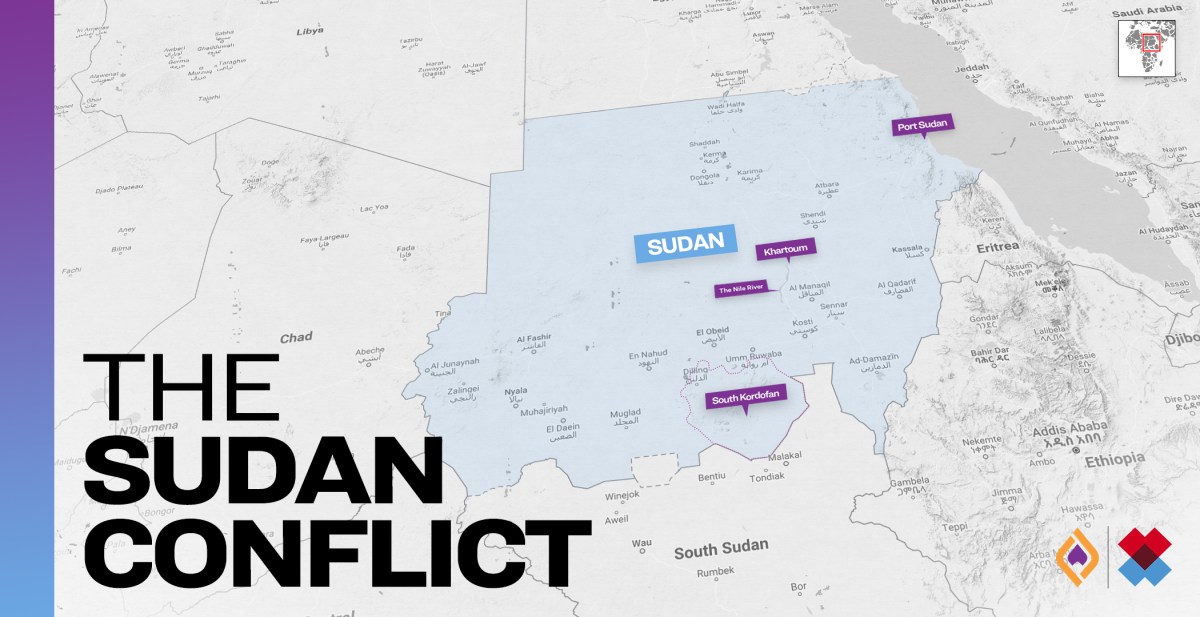

Despite the Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed in 2005, conflict continues in South Kordofan, a state in Sudan. A majority of men were killed, or they left their homes to fight, leaving women to run their households. These women faced many obstacles due to the patriarchal nature of society. They were not welcome in community decision-making spaces, which limited their ability to protect and provide for their families. Recognizing the need for these women to have socially appropriate spaces to hear information and discuss their concerns, Search turned the existing cultural practice of having coffee ceremonies into an opportunity for women to gather. In these gathering spaces, women from different ethnic groups shared their challenges. In doing so, they expressed, often for the first time, their deep trauma and realized they were suffering the same challenges despite being on different sides of the conflict. From this common ground, they formed women associations, from which they organized to advocate for female rights, building the society they all wanted to see from a united front.

The women also received economic empowerment training and support, strengthening their ability to take care of their families. After working with our targeted communities, 75% of women reported having increased access to social, economic, and political rights. In the communities Search targeted, 84% of women report having an increased opportunity to advocate for gender equality. By supporting marginalized groups to advocate and provide for themselves, Search is enabling sustainable development.

Key Moments Leading to Sudan’s Current Conflict

- In April 2019, the military forced President Omar al-Bashir to step down, following nationwide protests. Next, the military suspended the constitution and imposed a three-month state of emergency. A transitional military government was formed. However, protests continued because people wanted power to transfer to civilian authority. Two months later, militias killed 120 protestors in the Khartoum Massacre.

- In August 2019, civilian and military leaders signed a power sharing agreement for a three-year transitional period. The Transitional Military Council gave power to the Sovereignty Council of Sudan, which appointed Abdalla Hamdok as the prime minister of the transitional government.

- On October 25, 2021, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, took control of the government, dissolved the Sovereignty Council, and arrested Prime Minister Hamdok. His deputy commander was Rapid Support Forces (RSF) leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti. Public protests and strikes were widespread. Under international and internal pressure, General al-Burhan agreed to restore the Hamdok cabinet in a power-sharing agreement, with elections to be held in 2023.

- In January 2022, Prime Minister Hamdok resigned because he couldn’t form a new government. In December 2022, military and civilian leaders signed a preliminary deal to end military rule and enable a civilian-led transition to elections. A final deal was to be signed in April 2023, but there is disagreement as to how the RSF would be integrated into the ASF, and that the armed forces would be placed under civilian oversight. There is also a personal rivalry between General al-Burhan, who is favored by Egypt, and General Dagalo, who is supported by the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

What’s at Stake Regionally?

Egypt

Not only is Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi close to General al-Burhan, he is working with the Sudanese central government to regulate Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile. Both Sudan and Egypt rely on the Blue Nile for fresh water. Additionally, Egypt is one of the first places to which Sudanese displaced by the current violence flee.

South Sudan

Not only is South Sudan experiencing an influx of refugees, which strains its limited resources, but the current violence in Sudan threatens the South Sudanese oil industry on which the country’s economy depends. South Sudan exports 170,000 barrels of oil a day through a pipeline running through Sudan. The recent fighting has complicated logistics and interrupted transportation links between South Sudan’s oil fields and Port Sudan.

Chad

Chad, one of the poorest countries on the continent, already hosts 400,000 Sudanese refugees from prior conflicts. Thousands more have arrived from Sudan in the last few weeks, and Chad is struggling to meet their daily needs as hunger is widespread among its own population, and local food prices are soaring.

People in Chad also fear cross border raids by Sudan’s militias, who attack Sudanese refugees and locals, as they did during the Darfur conflict. Chad reports that since the latest conflict began, 320 paramilitary forces have entered its territory. Chad’s leadership also worries that Russia’s Wagner Group, which is operating in the Central African Republic, could threaten its own central government.

Ethiopia

There are periodic flare ups of violence along the fertile al-Fashqa border region, a disputed area of the Ethiopian – Sudanese border, which could now worsen if either side wants to take advantage of the intense chaos in Khartoum. Sudan already hosts over 50,000 Ethiopians in impoverished eastern Sudan. In addition, Ethiopia has finished about 90% of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Sudan and Egypt worry might reduce water flow from the Nile River to their countries.

Eritrea

Sudan hosts 134,000 Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers. Sudan is also a transit country for Eritreans fleeing forced conscription, which is sometimes extended indefinitely, keeping some male and female recruits in military service for decades.

Libya

Sudanese militia fighters engaged in Libya’s 2011 conflict. They returned to Darfur, where fighting continued until 2020. Libya is considered a transit country for migrants who want to reach Europe and for weapons flowing into Sudan, South Sudan, and beyond. Individuals and communities are now highly armed, intensifying conflict. As violence increases in Sudan, more displaced people will flee to Libya.

Global Interests

Inside Sudan, competing military factions and democracy activists have been seeking external support. Although loyalties are constantly changing, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, China, Russia, and the US, among others, seek to influence Sudan moving forward.

Because Sudan straddles the Nile River and is located on the Red Sea, the US views Sudan as essential to maritime security. Over 10% of global trade passes through the Red Sea. Sudan also holds immense mineral resources including gold, oil, and Arabic gum, which is used in food additives, paint, and cosmetics. China invests heavily in Sudan, building oil pipelines, Nile bridges, textile mills, and railway lines. Gulf Arab States such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia have invested in Sudan’s agriculture sector, airline industry, and strategic Red Sea ports. Russia wants warm water ports, too. In February 2023, it negotiated an agreement with Sudan’s ruling military to create a naval facility in Port Sudan to moor nuclear-powered surface vessels. Before the agreement can be ratified, a civilian government must be formed. In the past, the civilian transitional government had opposed the naval base in Port Sudan.

Say “Yes!” to Peace Built on Common Ground