Afghan women’s access to education – cut short

Rural Syrians’ access to medical care – cut off

Iraqi livelihoods – cut down, all casualties of violent conflict.

When we hear about these hardships, we want to help. You supported supplementary classes so young Afghan women could keep learning. You made the dream of a medical clinic in rural Idlib a reality, and you invested in Iraqi entrepreneurs so they could rebuild their livelihoods. You provided relief to meet the emergencies caused by violent conflict.

Some humanitarian emergencies, such as the earthquakes that pulverized Turkey and Syria and the Afghanistan floods, that washed away entire communities, are unpreventable. Others, such as the ISIS genocide of the Yazidis and the Syrian civil war, are. Ten years ago, if you gave money to a humanitarian aid organization, eighty cents of each dollar helped victims of natural disasters. Today, eighty cents of each dollar helps victims of violent conflict. Violent conflict is today’s primary cause of poverty, suffering, and forced displacement.

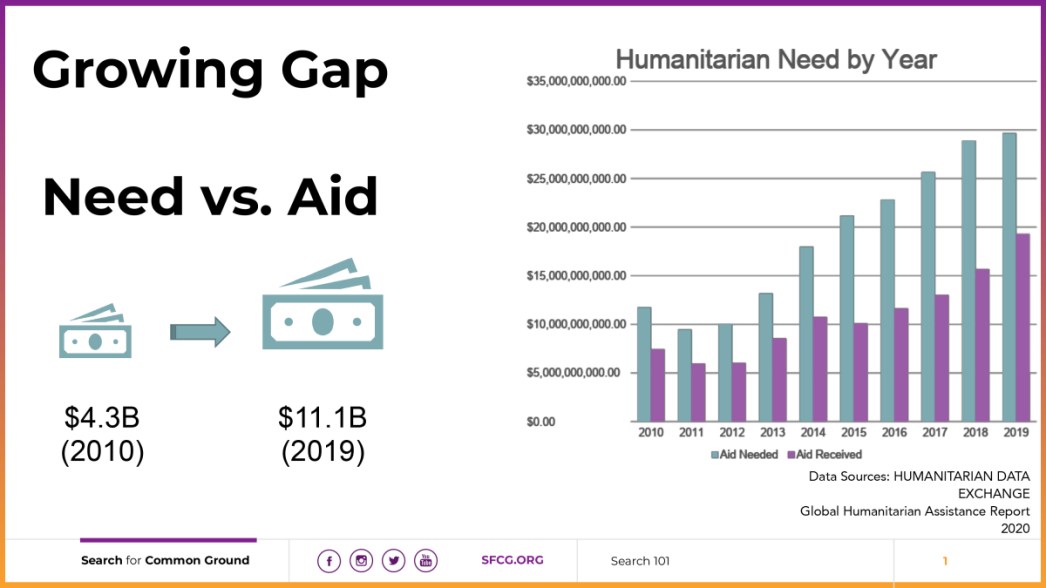

In the last ten years, violence has accelerated, as have humanitarian needs, while funding for humanitarian assistance has not kept pace. In 2012, the gap between total humanitarian need and available funding was 4.3 billion dollars. By 2019, that gap had almost tripled to 11.1 billion dollars. Because the gap between what is needed and what is provided grows yearly, we need to get better at preventing violence before it sparks.

When we prevent violence, measures of well-being such as life expectancy increase while child mortality rates decrease at an impressive rate, showing how peacebuilding and development aid exist in a virtuous cycle. Sustaining development gains requires peace, and peacebuilding makes development possible. Healthy societies can withstand destabilizing conflicts so conflict does not morph into violence.

Peacebuilding? Isn’t that like Tree-hugging?

The field of peacebuilding is challenging to describe because peace is difficult to describe. Our lived experience shapes our idea of peace. For some, peace is having a house made of concrete instead of mud because cement walls promise you won’t be displaced again. For others, peace is having enough food on the table to feed your kids. Cement walls and full kitchen pantries are outcomes, but how do we manifest these outcomes? At its core, peacebuilding supports processes that transform conflict into cooperation.

Conflict is inevitable because people have different interests and priorities, and their differences produce friction when they gather. Friction is not inherently bad, but conflict mutates into violence when it is managed poorly. When friction is managed well, conflict encourages people to rely on one another to solve a shared problem. It catalyzes social progress if all the parties in conflict work together to find a solution. When the solution benefits everyone in conflict, everyone has a reason to safeguard it, ensuring its sustainability. Having successfully worked together to solve an initial conflict, people on opposite sides of dividing lines deepen their trust and willingness to cooperate on the next shared challenge. That’s why peacebuilding focuses on processes and not outcomes. We call this process the Common Ground Approach.

How You Know Peacebuilding Works: Measuring Efforts

In the first half of the twentieth century, the medical sector shifted from treating disease to preventing disease to promote a healthy lifestyle. In order to define a healthy lifestyle, medical professionals agreed to measure certain vital signs to assess the health of a body (think temperature, heart rate, pulse, and blood pressure). Measuring these vital signs sets a baseline for how a body would function in the face of a destabilizing shock such as an infection. Would the body rally, or would it need an intervention?

Borrowing from the medical profession, the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize-nominated Search for Common Ground developed the Peace Impact Framework to measure the vital signs of a healthy society. This framework helps predict how a society will weather a crisis such as a pandemic, a natural disaster, or a terrorist attack. Will it rally, or will it descend into polarization or violence? The Peace Impact Framework has been implemented by 70 local, national, and international organizations across 30 countries in their peacebuilding work.

Consulting with peer organizations, scholars, policymakers, and the communities where it works, Search determined five vital signs of a healthy society. They include a measure of physical violence (because violence often begets more violence), agency (do people feel what they do impacts their future or do they feel hopeless?), polarization (how much do different communities trust one another?), institutional legitimacy (how much do people trust the police, the judicial system, the media?), and sustainable resourcing (are budgets spent on reactive measures, such as more police or more prisons, or are resources allocated toward proactive measures such as violence prevention training to foster healthier communities?).

Search measures its effectiveness according to three metrics: standard measures, such as the UN’s measure of a country’s level of violence; reflective practice, asking peacebuilding practitioners, leaders, and peers what they observe in their regions; and everyday lived experience, asking the communities with whom Search works to define progress because progress, like peace, differs by local context.

Search’s Common Ground Approach in Action

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) used to be known as the capital of sexual violence against women, as described by a UN special representative. Over 50% of the perpetrators were members of the military or the police. Search built trust between the community and the police and military through community engagements such as community theater performances, soccer tournaments, and the media. In this way, the community and the police sat together to watch something, and then they would have a conversation. From those conversations, community members and the police co-developed scorecards to define what meaningful improvements in police behavior would look like. In some parts of the county, the scorecards were used in performance reviews or to determine promotions.

By building trust and working together toward a shared solution, a breakthrough happened. The DRC instituted national reforms to the police and military. The training that Search had developed became part of the mandatory orientation for police and military officers, with over 200,000 officers participating. Within ten years, 94% of people interviewed thought the army provided better protection, 80% of respondents thought the police treated them respectfully, and the police reported that citizens now called them for help.

Peace moves at the speed of trust, which takes time to build and, like development gains, is easily destroyed. Peacebuilding starts with individuals understanding one another’s differences so they can act on their commonalities and make their lives better. Relief aid is a lifeline for vulnerable people, and we’ll continue supporting those in need with food boxes, blankets, hygiene kits, job skills training, and entrepreneurial investment to stabilize their lives. But real progress requires the audacious work of peacebuilding. Supporting both development aid and peacebuilding initiatives is how we will build the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible. Won’t you join us?

Preemptive Love + Search for Common Ground = An Unprecedented Force for Peacebuilding