Episode 1: The Longest Night

Experience one of the darkest, most-terrifying nights in Preemptive Love’s history: The night our entire aid team was nearly killed. The night we were caught between an ISIS convoy and US air strikes that mistook us for the enemy.

Share this episode

Show Notes

In this episode, experience one of the hardest, most-terrifying nights in Preemptive Love’s history: The night our aid delivery team was nearly killed. The night we were caught between an ISIS convoy and US air strikes that mistook us for the enemy.

You’ll hear from team members who nearly lost their lives that night. You’ll hear about us frantically tweeting coordinates to the US military, trying to get them to stop the bombing.

But most of all, you’ll hear about how, even in the face of death, and in one case, even coming face-to-face with ISIS, we chose to love anyway.

What happens when ISIS attacks your team’s aid delivery truck in the middle of the Iraq desert? And what do you do when, that same night, another aid vehicle bringing basic necessities to desperate people, gets shot at in the middle of a US airstrike—mistaken for the very ISIS fighters attacking your team?

Travel with us back to 2016 to experience a pivotal turning point in our organization’s history.

Experience a night in Iraq that made us press into pain. A night we’ll never forget. A night that changed…well, everything.

In our first episode of the Love Anyway podcast, you’ll meet:

-

- Erin: Preemptive Love’s senior field editor in Iraq, she brings experience and compassion as the host of our Love Anyway podcast.

- Jeremy: Co-founder of Preemptive Love, he pressed into pain at a pivotal point in Preemptive Love’s history, deciding to send an emergency aid delivery team into the Iraqi desert.

- Ihsan: Then a new member to the team, he left his young wife and child to go on a food aid delivery that went terribly wrong.

- Sadiq: Refusing to leave his stranded delivery truck, he risked his own life to protect food for vulnerable families in Fallujah who needed it most.

- Ben: Running Preemptive Love’s U.S. communications from home in real-time as his team members were attacked by ISIS and US airstrikes, he learned to press into pain, even when he felt helpless.

Discussion Questions:

- Erin says that in hard conversations, we often use the language closest to our heart. How have you experienced this phenomenon in conversations (and even conflict) with others?

- Ihsan could have chosen the comfort of working strictly from an office, but he didn’t. Instead, entered into a bigger story. What surprised you about his decision? Could you relate more to Ihsan or his wife?

- The long night in the desert taught the Preemptive Love team what it looks like to press into pain when the stakes are high. When have you pressed into pain in your everyday life? What did you learn?

- Feeling far away and powerless, Ben could have turned off his computer at the end of his workday. If you can’t control the larger events happening around you, what’s the point in sitting with uncomfortable feelings? How can you resist complacency?

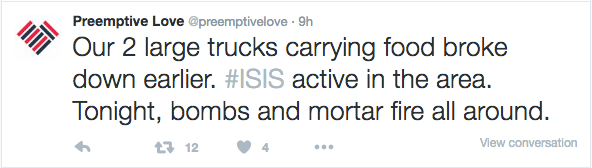

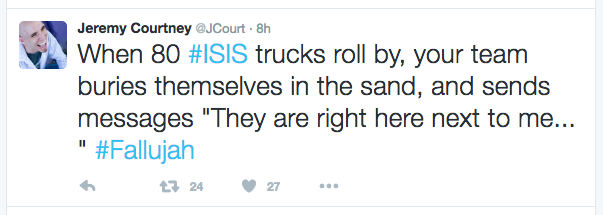

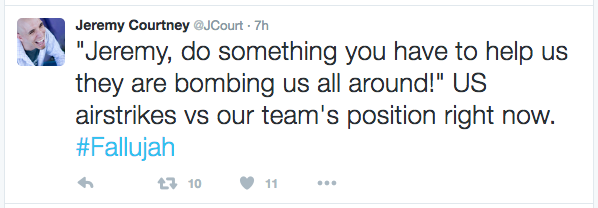

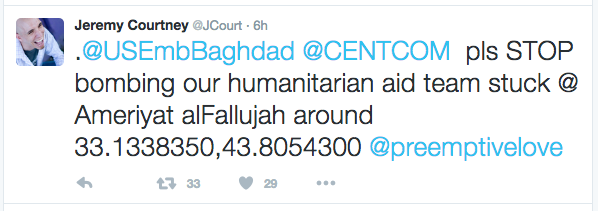

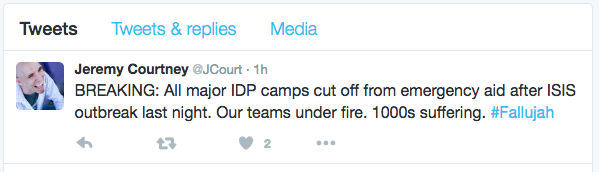

Urgent Tweets from The Longest Night:

More Photos:

Love Anyway is written and produced by Kayla Craig, Ben Irwin, and Erin Wilson. Skip Matheny is our digital production director. Dylan Seals is our sound engineer. Jeremy Courtney, Jessica Courtney, and JR Pershall are executive producers. Special thanks to Sadiq Al Rumaithi, Ihsan Ibraheem, and Sarmad Saman.

Don’t miss an episode. Subscribe now on apps like Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

Additional Resources

Full Transcript

Ihsan: That was an airstrike…it was so close. We were almost killed.

Erin: That’s Ihsan Ibraheem. He does program documentation for Preemptive Love Coalition. You just heard his message to us, seconds after being targeted by an airstrike.

What happens when ISIS attacks your team’s aid delivery truck in the middle of the Iraq desert? And what do you do when, that same night, another aid vehicle bringing basic necessities to desperate people, gets shot at in the middle of a US airstrike—mistaken for the very ISIS fighters attacking your team?

I’m Erin Wilson, Preemptive Love Coalition’s senior field editor in Iraq, and this is the Love Anyway podcast.

This season, we’re pushing beyond the simple story. We’re pushing beyond “us vs. them.” We’re sharing stories of how people in Iraq, Syria, and on the frontlines where you live are choosing to love anyway. We’re testing the limits of preemptive love and seeing how far it can take us toward a more beautiful world.

Meet Jeremy Courtney, co-founder of Preemptive Love Coalition.

Jeremy: This first story we’re going to share is going to challenge assumptions about what it looks like to do this kind of work, to show up for the other. To love your enemy…and not just the enemy that turns out to be a friend once you get to know them, but the real enemy.

This is also the story of one of the hardest, darkest, most-terrifying nights in our 10-plus year history, the night our entire aid team was nearly killed doing this work. The night we were literally caught between an ISIS convoy and US airstrikes that mistook us for the enemy. You’ll hear from members of our team who nearly lost their lives that night.

You’ll hear about us frantically tweeting coordinates to the U.S. military, trying to get them to stop the bombing. But most of all, you’ll hear about how, even in the face of death, and in one case, even coming face-to-face with ISIS, we chose to love anyway.

Erin: Today, you’re traveling with us back to 2016 to experience a pivotal turning point in our organization’s history. You’re experiencing a night in Iraq that made us press into pain. A night we’ll never forget. It’s the night that changed…well, everything.

This is episode one: The Longest Night.

It was supposed to be a normal aid delivery. On June 28, 2016, two trucks were carrying 100,000 pounds of food for those who fled the Iraqi city of Fallujah—about an hour due west of Baghdad. Our destination was one of the neediest, most under-served displacement camps in Iraq.

Now, Fallujah isn’t just any Iraqi city—it had a reputation. For a long time, its residents had felt disrespected and marginalized by the rest of the country. Fallujah became known as much for its political rebels as its many mosques. When ISIS first came on the scene in Iraq, Fallujans were initially sympathetic to their cause. They knew what it was like to be a serious underdog. And then in 2014, the situation turned, and Fallujah became the first city in Iraq captured by ISIS.

In fact, we had an international team of juvenile heart surgery specialists on their way to Fallujah when the city fell to ISIS. We had to quickly make phone calls and cancel a heart surgery mission in the city.

ISIS besieged Fallujah for two-and-a-half years. When Iraqi forces fought to take the city back, it was like a dam burst. In a 72-hour period, tens of thousands of residents–who had been starving–poured out of the city, fleeing for their lives. No government, no agency was ready for that number of people to flee in such a short period of time. Many of them wound up in hastily built displacement camps in the desert, where there was no aid waiting for them.

To be honest, within Iraq, there was some reluctance to help the Fallujans. Some said this was what they deserved after sympathizing with ISIS early on.

What was true that day? That day there were tens of thousands of starving people, displaced into Iraq’s harsh desert, with nothing but the clothes on their backs and hardly anyone raising their hands to bring aid.

We raised our hands. And our local Iraqi staff and partners drove right into the turmoil to help.

Jeremy: One day, our team was taking a couple of semi-trucks into the desert to make a food delivery on the far side of Fallujah. One of the ways we had access to this conflict zone was this sort of military only road that had been off the beaten path. It was usually used by huge military vehicles, but our team was in regular civilian trucks. Right around the middle of the day, our semi trucks just got marooned. Stranded. Stuck in the sand. They just couldn’t get out.

Erin: After a few hours on the road, the delivery trucks were stopped, not by the typical holdups like security officials wanting to check permission letters, but by the road itself. The trucks were stuck axel-deep in loose dirt, and they weren’t budging. It was a perfect storm of bad roads and heavier than normal loads.

Members of the team spent hours trying to free the trucks, toiling in 110-degree heat—but with no success. It soon became clear to the team that they weren’t going anywhere.

Sadiq: We didn’t face any problems while delivering the aid but it was hard to see the people. Little children were hungry and sick, pregnant women were not provided with the most basic necessities they needed. It was a dirt road and the trucks got stuck in the desert. We tried. Actually, I was the one that tried to get the trucks out to follow the rest of the team. I made the team go ahead to the camp to organize displaced people until we could get the trucks out. I tried my best to get the trucks out, but nothing actually worked because of the lack of equipment.

Erin: Sadiq, he worked with our local partners. He was the team leader and logistics manager for many of our relief deliveries. He’s a soldier turned relief worker. He was leading our convoy that day.

When Sadiq realized he and his team were stuck, he refused to leave behind the tens of thousands of dollars worth of aid destined for his fellow Iraqis who had suffered at the hands of ISIS. He was determined to get the food and supplies to those who fled Fallujah while Iraqi forces fought to recapture the city from ISIS.

When the battle reached the city, and thousands fled on foot, it was an extremely dangerous proposition. They risked sniper fire, land mines, and more. Most fled with nothing, and when they reached the hastily set-up camps, often there was nothing waiting for them.

Nothing. No food to eat. No water to drink. No mat to sleep on.

Sadiq refused to abandon his mission. He hunkered down for the night in the cab of the truck.

So there they were. A team agreeing to split into two. They could have never imagined what would happen both to Sadiq and the truck drivers, or the team that departed trying to get back to Baghdad. Why did Sadiq insist on staying behind?

Sadiq: The team, my group, told me that this place is dangerous, and we had to go back to Baghdad. We would return later—the trucks could stay in the desert with the driver. I was the team leader, I was responsible for the food for these hungry people.

They were people from provinces that were dear to our hearts. So it was hard for me to go rest, and leave the supplies in the desert. I decided that I wouldn’t leave them. I would stay in the desert because I believed in this cause.

Erin: The conditions in the desert that night were not good. It was hot, uncomfortable, and as both teams would soon find out: it was more dangerous than they could have imagined. At this point, Jeremy Courtney was at home in northern Iraq. His phone began buzzing.

Jeremy: As the day wore on…pretty soon it was dusk, the desert is still considered to be a pretty dangerous place in the middle of the night.

Right as they approached the outer gate back into Baghdad, there’s this breaking news, I guess, military intelligence, that a massive convoy of ISIS fighters had been found in the desert. Had been spotted in the desert. I guess the working theory was they were trying to make a mad dash to Syria. See if they could get out of the country and get free. To protect Baghdad, they locked all traffic out, our team was still on the outside at that point in two different groups. One at the trucks that hadn’t moved all day long, and the second was grouping at the city gates trying to get back in.

So we’ve got two groups locked out in the desert right now. Best we can tell, 100s and 100s of cars of ISIS fighters somewhere around the desert. It was just military intel, initially, and then the bombs started going off.

I remember this one message that came back from Sadiq, “Don’t worry. We know what we’re doing here. We’ll strip down to underwear and bury ourselves in the sand, and just get far off from the trucks as these ISIS guys roll through.”

Sadiq: I told the drivers to get down on the ground. When they got down, I asked them to take off their shirts. The ground was rough and empty…there was nothing that could help you hide.

There was one thing that I tried, hoping that it would help me. I put sand on my body, hoping that they wouldn’t see me. The good thing for me was that their lights weren’t bright, so the helicopter couldn’t see us. I put sand on my body and ISIS vehicles came in front of me, next to the trucks. The helicopters shot at them, and the trucks shot back at the helicopters. I heard the gunshots echoing inside my head, you could hear the sound of the bullets. So I closed my eyes and stayed on the ground. I couldn’t raise my head. I was afraid that if I raised my head, I would run away…I wouldn’t be able to control myself.

Erin: A former soldier, Sadiq used his military training to prepare for a hard night. Burying their bodies in the sand wasn’t like bedding down for the night at the beach. When we’re talking Iraqi desert, we’re not talking about rippling sand dunes. Imagine hard dirt. Even harder stones. Scorpions ready to bite. For this to be his best option was saying something. It was not a comfortable solution.

It was a last resort. Jeremy waited. And then a text came through.

Jeremy: At some point, we got this message that said something to the effect of, and you could almost hear the whispered tones of the text: They’re right here. On top of us.

Sadiq: I saw light spread across the desert. There was about 3 meters between every light. It was almost midnight, and the lights were weak, but they were getting closer. I told the officers on the phone, “Don’t be afraid. The Iraqi army is in the desert and coming towards me.” They said, “Where’s the Iraqi army?” I told them that the desert was full of vehicles loaded with weapons. They said that these were ISIS. When they said that these were ISIS, I realized the danger—and ISIS was coming towards me.

Jeremy: And I don’t know if it was just the…the need to send off what was assumed to be his last message, but Sadiq just had to get word out, that ISIS had arrived. That the thing that we had feared most, the ISIS convoy, had rolled up on him and the drivers and they were right there, and we’d later find out right there meant 15 feet away.

Erin: A massive ISIS convoy tore through the desert. Part of the convoy—around 80 vehicles—drove right toward Sadiq and the trucks. In such flat land, the trucks became an impromptu rendezvous spot for ISIS members driving in the dark. In fact, they stopped close enough to Sadiq that he could hear their conversations on their cell phones, while he and the drivers silently prayed they’d survive the night.

There he was, in the middle of the desert, as a military helicopter took aim at the ISIS convoy, destroying many vehicles and forcing the rest to flee. While Sadiq held his breath, Ihsan, a member of the Preemptive Love Coalition team, was in the group of vehicles trying to get back to Baghdad. But with news that ISIS was attacking, officials shut the city gates and refused to let anyone pass. Ihsan was stuck. Again.

And Jeremy would soon learn that his team would come under attack not once, but twice on the very same night. The night was turning to dawn, but the darkness was just beginning.

Ad: Hi friends. A quick break to share about our Preemptive Love Shop, one way your love is remaking the world. I’m Jessica Courtney, co-founder of Preemptive Love and our shop features all natural soap made by refugees, hand-embroidered tea towels, and apparel. With each purchase, you help fund our work on the frontlines. We’re excited to offer the Love Anyway podcast listeners a special 20 percent discount off one item with the code PODCAST. Find it at https://preemptivelove.shop and enter the code PODCAST for 20 percent off. Okay, back to the story.

Erin: So what happened? How did what was supposed to be an ordinary aid delivery turn into the most dangerous night in Preemptive Love Coalition history? Ihsan and the other half of our team soon learned they wouldn’t be returning home that night. Instead, they were spending the night on a concrete slab outside a military checkpoint between Fallujah and Baghdad.

Erin: The whole area was on lockdown because of the ISIS attack. No one was allowed through the checkpoint. Our team was stuck—vulnerable and exposed.

Jeremy: Ihsan was this amazing new guy that we had just managed to bring on board from a local TV station. We had been interested in finding someone local inside Iraq who had video skills to help us beef up what we were doing in terms of documenting and telling the stories from the people, of the people, who were running for their lives from ISIS and various militias. And what our community around the world was doing to show up and help these friends…so Ihsan joined the team, and he had mostly had a desk job, an editor type guy who sat behind a screen and edited video.

He, for his entire life, had been spared from the violence of war. He hadn’t seen much violence in Iraq himself, and we were trying to ask him how willing are you to go to the frontlines? Initially, he was pretty reluctant. He was willing to come on board and join the team as long as we didn’t send him to the frontlines. That was his condition. He was newly married, had a young daughter, and trying to balance the responsibilities of a family on the one hand, and on the other hand trying to be part of this humanitarian team, trying to be a good Iraqi, someone who cared for his own people.

Erin: In fact, Ihsan had made a promise to his wife: He would do this job, filming and editing videos for Preemptive Love Coalition, but he wouldn’t go anywhere dangerous. But here he was: Unexpectedly on the frontlines, not knowing if he would see his wife and baby daughter ever again. I asked him to reflect on that night.

Erin: I want you to close your eyes for just a second. It’s 2016, you’re in the desert, it’s dark. You are thirsty. You can see tracer fire in the sky. One of your colleagues tells you to turn off your camera because he’s afraid the light on the back of your screen is going to get you all killed. Can you describe where you are at that point? You can open your eyes.

Ihsan: It was a hard moment. Fear was everywhere. You can see it in everyone’s face that this could be the end. Guilt, because we didn’t finish the mission. Because we left one member of the team behind. We can not reach him. We can not go again and help him. Fear of our families. How it will be when we go, for them.How they will take this.

The longest night we ever experienced.

Erin: Eight years into Preemptive Love Coalition’s existence, here’s what was happening from Jeremy’s perspective as co-founder and chief executive. He had sent his team to deliver aid and felt the weight on his shoulders when things started going wrong.

Jeremy: Somewhere in the middle of the night, I can’t even remember, it’s all one big blur of not sleeping and getting on the phone with every person I knew who could possibly help, and even more than me, other friends and partners going to bat, who had bigger networks and better access than I did, trying to ring the bells of various defense people and government people to get word one way or another: Please be careful as you bomb the cars locked out in this desert, because at least a couple of them are ours, they’re not all ISIS. When you do a lockdown like this you can’t just assume that every vehicle moving in the night is an ISIS fighter. So please, powers that be, be aware. That consumed a lot of the night.

Erin: Not just a lot of the night. The whole night. In fact, he was frantically tweeting coordinates. At around 7 a.m., Jeremy Courtney used his personal Twitter account to send out a public, personal plea to the US Embassy in Baghdad and the US Military Central Command.

Jeremy: As the one who so desperately wanted to be with these guys and essentially commissioned and sent them out into this scenario, I felt a grave responsibility in what they were going through.

Erin: Meanwhile, Ben Irwin, head of Preemptive Love Coalition’s US communications, was in his living room in Michigan.

Ben: When I first started getting the messages from Jeremy, you could see the tracer lights of the helicopter gunfire in the distance, but not nearly far enough in the distance to be comfortable. It was surreal. It was kind of like what I remember watching on cable news during the first gulf war…except it was my friends, people I care about. So here was a part of me on auto-pilot mode, trying to do what we had to do to keep up on the situation, but this also part of my brain thinking this can’t be happening, this isn’t real, this is TV, this is theatrics.

But it was very, very real.

Honestly, I felt very powerless. In one sense, if I could detach myself from what I was seeing, and the fact that it was friends and people that I care about that it was happening to…in one sense it was weirdly fascinating that I could be this connected to something happening so far away. As the situation got worse and worse and things got more critical, I realize there’s nothing I can do but watch and wait. When the first airstrike targeted our team and Ihsan messaged Jeremy and said, “My God, they’re killing us. And then his phone went dead.”

We didn’t know if it went dead because his battery was drained or if his phone went dead because of the airstrike or some other reason. We were just waiting at that point. It’s the most utterly powerless to do anything that I’ve ever felt.

Erin: Jeremy, he was in his home 250 miles away in northern Iraq, and Ben in the U.S., could only wait. Minutes felt like hours, with every minute ticking past in silence, hope began to dwindle. Ihsan and his team were not allowed to approach the buildings by the nearby checkpoint for shelter. They wouldn’t have provided much shelter, anyway. In the middle of an airstrike, buildings, cars (anything that rises from the desert floor, really) becomes a target.

Ihsan: It was like a continuous dark…nightmare might be the word for it. You need to be calm, you need to be quiet. You need to stay where you are, don’t move, don’t make sounds. You’re tired but you can not sleep. You’re thirsty but you can not drink. You want shelter but that shelter will kill you if you go to it.

Ben: Sitting on my couch after Ihsan’s phone went dead and we didn’t know why and we didn’t know what was happening..um..I actually started writing an annoue–what we’d share if the worst happened. What we’d share if some of the members on our team didn’t make it.

Erin: Feeling powerless, he did what he could, updating Preemptive Love supporters via our Facebook page. Ben continued to pray and wait. So did Jeremy. Fifteen minutes later, they heard something from Ihsan.

Ben: His battery had died, and that’s why his cell phone had gone out. [But] It had felt like an eternity.

Erin: There was a collective sigh of relief—Ihsan was alive. Ihsan recounted what happened in a call with Ben the next day. What you’re about to hear is the raw audio from that phone call with Ihsan.

Ihsan: I was on the ground, lying on the ground, believing that this is the shelter I should have, and all the team was separated on the area, between each of us was around 30 meters, after that my phone battery dead. Ahmed was on the other side taking cover by some small dirt on the ground and I run to him. I was running to him and taking cover with him, I said do you have Jeremy’s number? He said yes. Called him for me. I talked to Jeremy after that.

I was thinking that the fighter jet was about to hit us for the third time. And it was so scary because we have an Iraqi saying: Third time, never miss.

Ihsan: We were hit two times. We’re thinking the third time, maybe, it’s the end for us. After all of this, for about 15 minutes maybe, 20, there’s a jeep car coming and rescued us from the location.

Erin: Here’s where we are: Sadiq’s convoy, the one that stayed, was surrounded by ISIS. And Ihsan’s convoy, the one that tried to get into Baghdad, was attacked by what we believe was a US jet, trying to attack ISIS. Our staff already knew what it looked like to press into pain, after spending so many hours at the bedsides of children we helped to receive lifesaving heart surgeries.

That night in the desert taught us what it looks like to press into pain in a very different way, when the stakes are high.

Trauma doesn’t suddenly end, even if the triggering events do. After Ihsan spent the longest night of his life in the desert, he faced more long nights, talking through what happened with his wife.

Ihsan: After, in the car, my wife talked to me, calling me…she called. She said ‘What’s happened? Is everyone okay?’ I told her ‘Yes, we found a car…and they let us go. Oh thankfully. Thank God!’ I told her. ‘Okay, once I get to Baghdad, to the hotel, I will call you back.’

Erin: All through that long night of terror, Ihsan told his wife as little as possible. He wanted to protect her, to keep her from worrying. But he wasn’t used to keeping things from his wife.

Ihsan: I couldn’t just, ya know, keep this anymore. I needed to talk to someone…I went to the hotel, closed the room, and I explained this to my wife. She was crying. I was. And the only thing we keep saying is how thankful…to God. It’s a miracle. It’s a miracle. We saw those videos of airstrikes hitting targets—they don’t miss.

Erin: That was just the first of many hard conversations. The longest night in the desert was over, but the war was not. And our work wasn’t over, either.

Ihsan: After the airstrike, I told her, ‘This is the last time’. I don’t lie. This is maybe one of the things she knows about me. If I say something, I will do it. I told her that this would be the last time—but a month later I went back. And I went back. And I went back. Again and again. Mosul happened, and I went back…

Somehow she started to understand why I’m doing this. Why I went back again. She still telling me that ‘You said this is the last time. Why do you go back? Do we not mean more…to you than the work we do? Do you think so?’

Erin: Ihsan would give his life for his family in a heartbeat. His wife knows that. But in hard conversations, we often use the language closest to our heart.

Ihsan: I’m not a guy that has a rush to see violence, or to see war or something. It’s not that. But it’s—at this moment, this is what needs to be done. My parents, on the other hand, also was saying that this was not okay. ‘You are not going back to those places.’ But they know things. I know different things. Maybe similar things, but in a different way. And that’s what makes me go back.

Erin: We each acquire a special kind of knowledge when we experience extreme events. That knowledge carries us through long nights of pressing into pain.

Sadiq could have left the food-laden trucks in the desert and returned to the safety of Baghdad. No one would have judged him for it. But he didn’t give up. He personally made sure that the food reached starving families waiting in the desert for help.

Ihsan could have chosen the comfort of working strictly from an office, but he didn’t. Instead, entered into a bigger story. He could have chosen, like so many who experience severe trauma, to keep what happened bottled up inside him, to keep what happened from his wife. Instead, he invited her into this part of his story and opened up some really difficult conversations and deeper connection.

Feeling far away and powerless, Ben could have turned off his computer at the end of his workday, but he stayed with those uncomfortable feelings and stayed engaged with his teammates across the globe.

And Jeremy? Jeremy could have given up hope of doing this kind of work in Iraq. There are countless needs here thanks to decades of war. He could have decided that bridging the gap between those in the most need and lifesaving aid was just too hard. He could have decided that going to places no one else would go was too unpredictable, too scary, too costly. But he didn’t. We didn’t. Jeremy leaned into doing everything he could to keep his team safe while continuing to reach out to those others won’t.

And we still do.

Visit the show notes on our website at preemptivelove.org/podcast to see photos from that longest night in the desert, links to other stories of our work in Fallujah, and discussion questions to talk through this episode if you’re listening with friends.

In our next episode, we’ll find out what Sadiq did next, and what led him to take a risk to feed the same ISIS members who killed his friend. What does it actually look like to love our enemies? Join us as we peel back the layers of taking risks and doing hard things.

Ad: If you’re listening to this podcast, chances are you’re the type of person who shows up. Who shows up on the frontlines of polarization and division in your communities. Who chooses to love anyway. I’m Toni Collier, The Frontline Director with Preemptive Love Coalition. By joining our monthly giving community, you’re helping families in conflict around the world as you pursue peace where you live. Learn more at loveanyway.org.

Erin: I’m your host, Erin Wilson. Thanks for listening. The Love Anyway podcast is written and produced by Kayla Craig, Ben Irwin, and Erin Wilson. Skip Matheny is our digital production director. Dylan Seals is our sound engineer. Jeremy Courtney, Jessica Courtney, and JR Pershall are executive producers. Special thanks to Sadiq Al Rumaithi, Ihsan Ibraheem, and Sarmad Saman.