Season 2 | Bonus: How 9/11 Changed Us

Preemptive Love founder Jeremy Courtney hosts a reflective episode featuring a diverse collection of memories and experiences about 9/11.

Share this episode

Show Notes

September 11, 2001 changed everything.

We asked some of our colleagues from Iraq, the United States, and other parts of the world to reflect on their memories of 9/11. Some were just starting their adult life when 9/11 happened; others had to process it as children. Some watched from a distance as the Twin Towers fell; others were intimately connected to the loss felt on that day.

On this episode, you’ll hear reflections from:

- Jeremy Courtney, Founder and CEO

- Jessica Courtney, Vice President International Relations and Founder

- Saadia Qureshi, Frontline Coordinator

- Yemisi Adetunji, Vice President Finance and HR

- Audrey White, Design and Development, Sisterhood Collection

- Dane Barnett, Student and University Engagement Manager

- Ihsan Ibraheem, Program Documentation

- Diana Oestreich, Key Relationships Officer

- Charlene Winfred, Communications Officer

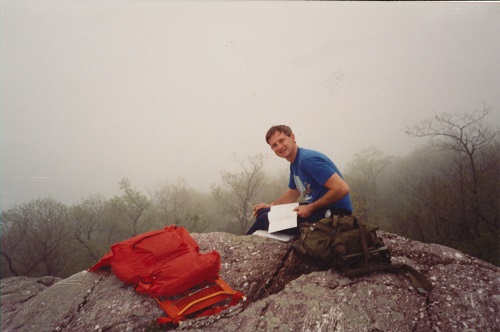

On this episode, Audrey shares that when she was six years old, her father’s cousin, R. Bruce Van Hine, lost his life at the World Trade Center on September 11. A firefighter with FDNY Squad 41, he was one of six men lost from the squad. He was 48 and left behind a wife and two daughters. He had completed hiking the Appalachian Trail in New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut. As he hiked the trail‚ he left Bibles in the shelters.

Every person has a story. Each year as this day arrives, we pause to remember.

We remember when we heard the news, where we were, how we felt. We remember the fear that rose in our throats, the fear the began to change the way we walked in the world, the way we saw each other. American or Iraqi, Muslim or Christian, adult or child, September 11 has shaped who we are and the world around us.

Read more reflections on 9/11 on our blog.

September 11 also set in motion a chain of events that led to the formation of Preemptive Love. As the United States launched into Iraq, to wage war against an enemy that had nothing to do with 9/11, we launched into Iraq to wage peace.

Later in September, we’re launching the biggest, most ambitious undertaking in Preemptive Love’s 12-year history.

Later in September, we’re launching the biggest, most ambitious undertaking in Preemptive Love’s 12-year history.

We’ll be sharing a film, and a new book called Love Anyway.

The story we have to tell, in many ways, began on September 11. It’s a story of exile, of losing the home we thought we knew, and of what happens when our temples come crashing down. And it’s a vision for how we can build something new from the ashes. A new kind of community where we take a step toward those we fear or misunderstand, where we start to live like we really do belong to each other.

On September 11, we remember all we lost that day 18 years ago. On September 24, we can take our first steps out of exile, together. And launch into a new way of living and being and belonging to each other.

Additional Resources

Full Transcript

Jeremy: September 11, 2001 changed everything.

Jeremy: 2,996 people were killed that day, including the 19 terrorist hijackers. Over 6,000 people were injured. And in the years since, as many as 2,000 first responders who bravely rushed into the danger have died from cancer and other diseases caused by exposure to toxic chemicals that day.

Jeremy: This is the Love Anyway podcast. I’m Jeremy Courtney.

Jeremy: The events of 9/11 launched the United States into not one but two wars, one of which is still being fought today. But more than that, September 11 profoundly changed our psyche. The way we look at the world… the way we look at each other.

//

Jeremy: The ancient Jewish scriptures tell the story of the day their temple was sacked by an invading army. The most defining symbol of the Israelite nation, and the Jewish faith, was lost… and on the heels of that loss came decades of exile.

Jeremy: On September 11, the closest things the United States has to a temple were targeted. The most defining monuments to its financial, military, and political power. The Twin Towers, the Pentagon, and what many believe was the intended target of United Flight 93, the US Capitol.

Jeremy: We’ve been stuck in a sort of exile ever since. Our identity, fractured. Our relationship to the world around us, broken.

//

Jeremy: September 11 also set in motion a chain of events that led to the formation of Preemptive Love. As the United States launched into Iraq, to wage war against an enemy that had nothing to do with 9/11, we launched into Iraq to wage peace. To try however we could to mend the wounds of war. To find a way out of our shared exile, together. To see if we really could create a country—or even a world—where everyone belongs.

Jeremy: We asked some of our colleagues from Iraq, the United States, and other parts of the world to reflect on their memories of 9/11. Some were just starting their adult life when 9/11 happened; others had to process it as children. Some watched from a distance as the Twin Towers fell; others were intimately connected to the loss felt on that day. These are their stories.

//

Jeremy: Saadia Qureshi helps organize monthly neighborhood gatherings for Preemptive Love. She is a Muslim American of Pakistani descent and a mother of two.

Saadia: I was driving to work, I worked as a Compliance Environmental Inspector. I had just gotten married two years prior to that. I heard the news and I didn’t even know how to comprehend what a building “going down” meant or what was happening. Then the second building collapsed. We were all in disbelief and cried together.

As a family, we were panicked at a different level as well—my husband’s brother had an internship in Manhattan. His building was three blocks away from Ground Zero. We were so scared because for a good couple of hours we couldn’t get hold of him. Finally, a cousin got through and thankfully he did not go into work that day because he was sick.

No one went out for inspections that day. And then it came—the official report that it was terrorism. Muslim terrorism. My boss at work asked if it was okay that I do not go on inspections for a little while, for safety reasons.

And then came the call to actions, from the Muslim community. Asking us to be careful, be diligent, be safe. Some of the top Islamic scholars even advised that if a woman in hijab feels unsafe going out in her hijab, that it would be okay to take it off. I didn’t take mine off. I was angry at the people who claimed to be Muslim and did this “in the name of Islam.” Those “Muslims” hijacked planes, also hijacked our religion. We were public enemy number one and it was due to some “Muslims” under the guise of Islam.

But we got through it, sort of. We went to vigils, tried to stay vigilant, tried to prove to everyone that we aren’t “them.” In the beginning, we laid low didn’t make too much noise, because we didn’t want any eyes on us. And then we decided that people needed to know us. So we tried to be more involved in our community. We made a conscious effort to be present for others. We would get the occasional side-eye, our kids would get racist comments made to us. But we decided that to change the narrative, we had to be a part of creating the new story.

We told our children that it was just bad luck. That the people who did this had nothing to do with Islam or its teachings. That killing an innocent person is like killing all of humanity. That we, as good Muslims in America, need to be good humans. The people who did this were neither, and for them to use God as a reason for doing this is a betrayal to God and humanity. That there is good and bad everywhere but this was a particular type of evil because the short-term and long-term effects were so vast. And sadly, we keep having these discussions over and over again after every mass shooting, after every tragedy caused by humans.

//

Jeremy: Yemisi Adetunji was born in Nigeria but came to the United States as a child. She was an MBA student in California when the 9/11 attacks occurred.

Yemisi: I remember watching the TV right after the first tower was hit. And I watched live as the second tower was hit. I was numb. I felt like America had been caught unawares. I stayed glued to the TV from morning until bedtime, just stunned. I had a job interview the next day in Chinatown, close to downtown Los Angeles. There was no one on the roads and as I approached downtown, I saw cops guarding public buildings.

I felt the effect of 9/11 personally when I flew. I regularly flew to visit my family and my airport experience had always been uneventful. But after 9/11, I was always “randomly” selected for screening. I knew it was because of my last name but I didn’t mind. If this is what it would take to make us safer, then I was fine with that. I actually felt the safest, traveling the months after 9/11, because I knew security was at such high alert.

//

Jeremy: Audrey White works in our Iraq office and was just 6 years old on September 11, 2001.

Audrey: We were on our way to church. The pastor’s wife came out and told my mom and she tried to explain it to my siblings and I. She told us that “bad people had flown planes into buildings in New York and DC.” I didn’t really understand. I was too young to remember time before that, how travel was. I only knew how it was after. I remember seeing Osama Bin Laden’s face on a magazine cover and afterward having nightmares.

My father’s cousin was a New Jersey fireman and he lost his life responding to 9/11. We went to his funeral. They had fire trucks with ladders up in salute for us to walk under them. Before the funeral, we walked around Manhattan and it was eerily silent, covered in dust, and guarded by soldiers.

I didn’t pick up anti-Islam extremism, but it was slowly, subtly instilled that Muslims are the “bad guy.” I grew up in a church that taught us to combat and argue against Islam.

And now living in Iraq, I’m learning how I can have so much in common with Muslims and have beautiful friendships with them. That there are extremists in any group but that’s not the whole story or where the story ends.

//

Jeremy: For Dane Barnett, who was 9 when the Twin Towers fell, the attacks of that day and the war in Iraq 18 months later became fused in his mind.

Dane:I woke up sometime after the first tower was hit and I remember watching the plane crash into the second tower. Later I watched the invasion of Iraq, at night, with the night-vision newsreels. Over the years, these two events became linked in my mind, I remembered them like they both happened on the same day, one after the other. I remember a vigil at our church shortly after the attacks and tying yellow ribbons around trees and hanging up flags at my house. It was blind patriotism. It shaped my mind as I grew up. In January 2002 I had a stroke. I was put on medication and I had a bad reaction and hallucinated.

And in my hallucinations, I was falling out of the Twin Towers—I was one of the ones who jumped. I remember how scared I was, screaming for my life, seeing the towers burning and my body falling between them. That day was so lodged in my 9-year-old brain that months later, that’s where my brain returned during those hallucinations. People talk about 9/11 being a shift to fear and to war… I don’t know that shift. I just know that posture. For the post-9/11 generation, we need to undo the grip of that day on our hearts. Not forgetting it, but to truly honor those victims we have to address the hate and fear that led them to be victims in the first place. To remember 9/11, it’s complicated. I don’t know my country or my community or my patriotism without it.

//

Jeremy: My colleague in Iraq, Ihsan Ibraheem, watched news of the attacks from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, unaware that his own country would be drawn into war in the aftermath.

Ihsan: It was evening and I was at home with my family. During Sadaam’s regime all houses had TV. There were only one or two stations available at the time—mostly news and propaganda stuff. They broadcasted 9/11 live through international TV stations. When we saw the attack, I remember I didn’t understand what was really happening. I didn’t know what it meant or what it would lead to. I didn’t think it would lead to war. We were surprised, but we weren’t worried. The news then cut to something else. I don’t think many people thought it would lead to war in Iraq.

//

Jeremy: Diana Oestreich was in the US military at the time—and she knew what the events of September 11 meant for her.

Diana: I was in nursing school. My professor walked in and turned on the TV and said, “Something is happening.” We saw the Twin Towers falling. As I was watching I realized that because I was in the military, this was going to change my life. My professor had a son in the military and she kept watching and within 5 minutes she canceled class so she could call her son. I knew because I belonged to the military that I wasn’t just watching a current event, that this had the ability to reach into my life and pluck me out of the life I knew. Two years later I got called up. I talked to another soldier who told me he had been in the Reserves and the day 9/11 happened he got called up, out of college, and he sat in a bus, for 2 years, in front of Ground Zero. He had not been back to his civilian life since the day 9/11 happened.

//

Jeremy: Charlene Winfred, who was born in Singapore but lived in Australia at the time, experienced firsthand what it was like to be profiled because of the color of your skin after 9/11.

Charlene: At around 1 in the afternoon the phone rang and my friend yelled, “turn on the TV!” and then hung up. I turned on the TV just in time to see a plane crash into a tower.

Fear grew and it found easy targets in anyone who looked like the “bad guy”—a brown, Muslim man. I’m biracial, 50/50 Indian and Chinese, but looking at me you’d never guess there was any Chinese. I look like the “bad guy” in some cases, as some customs officers have reminded me of. For a while when I disembarked from some airports in the US, I and whoever was with me were herded through the special queue for brown people.

Moving through communities all through the world I’ve learned to be good at making my already weird self palatable as possible to dominant groups. I won’t speak for everyone else who is brown, but particularly for me, it’s getting harder and harder to keep an even keel, to keep pleasing people as I get older. The demands of being, of trying to blend in, to be acceptable, are huge. It’s exhausting.

There has to be space to talk about this or the status quo gets maintained. My daily life is a reminder that kindness really does exist in the world. If you step back and look at the larger picture, yes, the world seems horrible right now, but we have people out there doing good work, it’s a sign of hope.

//

Jeremy: And for Jessica and me, 9/11 set us on a course that took us to the Middle East, and ultimately, to Iraq. Initially, to change the people we thought were the enemy. But often, when we move closer to those who are different—to those who believe differently, pray differently, or see the world differently—we discover that we are the ones who need to change.

That’s what happened for Jessica and me—and ultimately, that was how Preemptive Love was born.

Jessica: It was about three months after we got married that 9/11 happens, and what had seemed like the biggest rift in relationship with America in another country to me growing up was Russia, but what had seemed like the biggest rift. All of a sudden it became really obvious that that wasn’t the biggest rift. That the biggest rift that was being created in America was actually between Muslims and Christians or between America. And the Middle East, specifically Afghanistan and Iraq, and it didn’t make sense to me that the decision of a few people was going to change the life of millions of people on the other side of the world from America, just because they happen to have the same beliefs or same religion, maybe even not the same beliefs but the same religion as the people who were terrorists. And it became at that point, it became a really natural shift that the people that were the underdogs, the people that we loved the least, were the people in the Middle East.

Jeremy: I don’t really remember talking about Islam much before September 11th, 2001. But from that moment on, it just seemed like everything in our world, a lot of America was zeroed in on this conversation about Muslims and Muslims as terrorists in particular. And America went off to war fairly soon after that.

We didn’t think we were part of that kind of way of responding to September 11th, so we went in a slightly different direction. We wanted to address the problem of terrorism and what at the time we would have probably called the problem of Islam. We wanted to address that by making Muslims into Christians.

I would have to confess that we also didn’t want Muslims in the world. We also didn’t know how to live at peace with Muslims.

We chose not to pick up the gun to respond to September 11th and to respond to terrorism, but we picked up weapons. I would say we weaponized our lives in some ways and moved overseas for the purpose of getting rid of Islam, for the purpose of getting rid of Muslims.

We didn’t want to kill anybody. We still wanted Mohammed, this friend on the other side of the table from me. We still wanted Mohammed to be alive and well in the world. We just didn’t want him to be alive and well in the world as a Muslim. We wanted him to renounce all of that and come over to our side.

There was never any sense that we would also change, that we would divest or give away what we knew to be true. That we would have to relinquish some of our ideas, our strongly held beliefs.

A couple of years after moving overseas and trying to do this, I remember just going facedown on the ground and crying out to God in frustration and anger, “I’ve been here faithfully doing this work for more than 2 years. I know the language really well and I’m giving my life to this and I’m out every day in the markets and streets.” And I’m facedown just crying, “Why me? Why me?”

There was a voice. And the voice said, “It’s because you don’t love them, Jeremy. Sure you love to be right. To be thought highly of. That you have all the best words and the best arguments and you’re brave. But you don’t love this guy Ahmed or Mohammed, on the other side of the table from you, for who he is today. Full stop.”

I saw my fists come down and open up into an open-handed embrace. I stood up off that floor and I knew I was transformed.

I walked out of the conference, out of the hotel. And we moved to Iraq. And I was a completely different person.

//

Jeremy: Later this month, we’re launching the biggest, most ambitious undertaking in Preemptive Love’s 12-year history. We’ll be sharing a film, and a new book called Love Anyway. The story we have to tell, in many ways, it began on September 11. It’s a story of exile, of losing the home we thought we knew, and of what happens when our temples come crashing down. And it’s a vision for how we can build something new from the ashes. A new kind of community where we take a step toward those we fear or misunderstand, where we start to live like we really do belong to each other.

On September 11, we remember all we lost that day 18 years ago. On September 24, we can take our first steps out of exile, together. And launch into a new way of living and being and belonging to each other.

I hope you’ll join us by going to loveanyway.com.

My name’s Jeremy Courtney. This is the Love Anyway podcast. Thanks for listening.