Season 2 | Episode 2: Love Beyond Borders

Immigration is a complicated topic, even for adults. Some of us are afraid to say the wrong thing. Others of us fear those who are different. How do we talk about immigration with family members? With kids? On this episode, we start by listening.

Share this episode

Show Notes

Immigration is a complicated topic, even for adults. Some of us are afraid to say the wrong thing. Others of us fear those who are different. How do we talk about immigration with family members? With kids? On this episode, we start by listening.

On our second episode of the season, we hear from José Chiquito, a college student who came to the US with his family as an undocumented child. We also talk with Luisa, whom our colleague Billy Price met at the US-Mexico border after she traveled with her grandchildren from Honduras to legally seek asylum. And Laura Pontius, an immigration attorney, shares why the language we use about immigration matters.

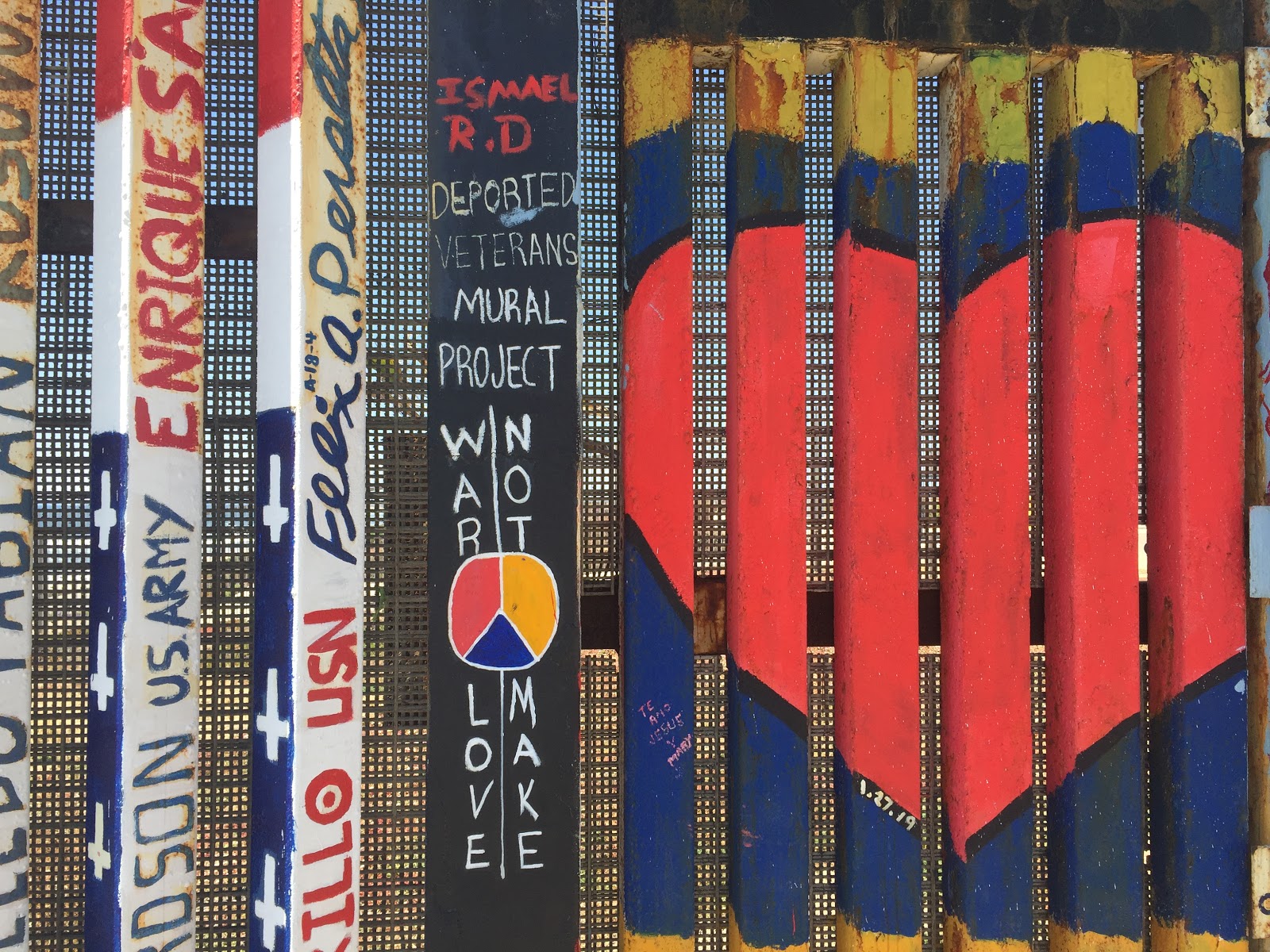

We also provide a field update about the aid and assistance you’ve made possible to families seeking asylum on the US-Mexico border. As the crisis evolves, this is what it boils down to: Families are risking danger, desperately trying to find refuge. And we can be the people who choose to love anyway on the US-Mexico border.

Listening to people like Luisa and José is a good start to understanding how to broach topics such as immigration with our friends and children, because stories connect us, erasing the lines between us vs. them.

Use the special code PODCAST for 20% off one of our new Love Beyond Borders shirts. Every shirt funds our peacemaking work on the frontlines of conflict on the US-Mexico border, in Syria, Iraq, and beyond.

Learn More:

- José’s podcast (Ecotiva Radio)

- Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (US Citizenship and Immigration Services)

- Key Findings of US Immigrants (PEW Research)

- Renewed Call for an End to Family Separation at the Border (American Academy of Pediatrics)

- The Dream Act, DACA, and Other Policies (American Immigration Council)

- FAQ’s About Unaccompanied Children (US Department of Health and Human Services)

The Love Anyway podcast is written and produced by Kayla Craig, Ben Irwin, and Erin Wilson. Skip Matheny is our digital production director. Jonny Craig is our audio editor. Dylan Seals is our audio mix and mastering engineer. Our executive producers are Jeremy Courtney, Jessica Courtney, and JR Pershall. Special thanks to Billy Price, José Chiquito, Kim Mierau, Eileen Rose, Laura Pontius, and Luisa—whose name was changed to protect her identity. Our theme music is by Roman Candle.

Don’t miss an episode. Subscribe now on apps like Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

Additional Resources

Full Transcript

Laura: So I think it’s important for people to know that these mamas and papas, and aunts and uncles, and grandmas and grandpas are coming because it’s their last resort. They are doing everything possible. They’re fulfilling their responsibility as caregivers of children and families to do whatever is necessary to make their children’s lives better and safer.

INTRO MUSIC

Erin: Immigration continues to be at the forefront of political debate, fraught with rhetoric and scare tactics, around the world and in the US. And the media we consume, the language we use…it all matters.

What if showing up starts with listening?

MUSIC

Erin: Today, we’ll hear from Jose, a friend who came to the US with his family as an undocumented child. We’ll hear what he wishes others knew about his life through the eyes of a young boy caught between two worlds, and how his experiences as an immigrant motivate him now as a college student. We’ll also hear from Laura Pontius, an immigration attorney and educator, who knows how much language matters.

But first, we want to update you on the work Preemptive Love is doing on both sides of the US-Mexico border, and the emergency assistance you’ve made possible.

The need has shifted to Juarez, Mexico, where we’re focusing our efforts to support local long-term shelters implementing sustainable solutions that will help minimize running cost, create a more dignified space, and serve asylum seekers. Because of your contributions, we’ll also be providing legal assistance to help them understand their current situation, their rights as asylum seekers, and then support them during their court case.

MUSIC

Erin: My colleague Billy Price recently spent time at the US-Mexico border, visiting shelters in Juarez and connecting with Preemptive Love’s partners on the ground to provide much-needed aid. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, 11,800 minors, including both children separated from their parents and those who arrived alone are currently in their care, in their network of more than 100 shelters, in 17 states. This doesn’t include the number of children staying in shelters in Mexico.

Billy told me about a woman he met in Mexico, whose family is now bisected by the US southern border.

Billy: Yeah, so, for her safety and privacy, we’re going to call her Luisa. She’s a short, tender woman from Honduras, about 60 years old. And when we met her, she had been doing laundry by hand at a long-term shelter. At this time of year, it was hot inside and out and there’s really nothing to do for many of the refugees other than laundry, helping with meals, so there’s not much choice but to be sitting around in the heat. Luisa came to apply for asylum with her three grandchildren. Her daughter, the mother of the children, came to the US about 6 years ago. But, for Luisa, life in Honduras was increasingly unsafe. Luisa’s husband, the girls’ grandfather, was abusive, the father of the grandchildren was long gone, and a gang member had been harassing the oldest of the 3 girls. So, Luisa came here to legally seek asylum.

Luisa: I love my girls so much. I have been there by their side. I taught them how to walk, how to eat. I taught them how to value things and life. They are growing, they are studying and learning how to value life. Since my daughter came here, I was in charge of them. I have been their support.

Billy: She was the sole caretaker for her granddaughters. But when she filed her paperwork, she didn’t have evidence of any of it, nor of the gang threats to her family. So she didn’t have tangible proof, of anything.

Luisa: The judge told us we needed to present evidence, but I don’t have evidence. I just said what happened to me. The girls were in danger.

Billy: This is so common. There’s no evidence or paperwork because Honduras is such a mess, the government services there are often inaccessible or non-existent, police aren’t available or are often untrustworthy, people are robbed of their evidence or paperwork while migrating… Our system expects people to arrive with quote 1st world documentation, but that’s exactly what they have not had and why they are in need. So instead they charged her with a crime, and her granddaughters, one is 15 years old, one is 12, and the youngest is 7…they were separated from her by the officials.

She told us that when they crossed the border in El Paso, they were told to put everything they had with them in a large container.

They were left with nothing. [pause] And then they were separated.

Luisa: They took the girls from me. The little one said, “No, mama. I don’t want to go.” I raised those girls.

Billy: When we talked with her, it had been over 250 days since she had seen her children. She has been waiting since October 2018.

Luisa: I kept asking them about the girls. Where were they? They said they couldn’t tell me anything because I had committed a crime bringing them here, that I wasn’t a relative to them.

Billy: We spoke with Luisa for nearly an hour that day. And we learned so many of her personal stories like her time making tortillas and selling paletas to provide for the kids. And she told us about a time when she was estranged from her daughter. She talked about her daughter returning home with these three grandchildren, and she spoke of their reunion with so much warmth and hospitality and mercy and love. And years later, after that reunion. She had to make an incredibly difficult choice. And all she wanted was to do what’s right for her grandchildren and for her daughter. And she traveled from Honduras, through Guatemala, and through Mexico, just the four of them. And she made it all the way to our border. And now she’s alone.

Billy: One of the things that preemptive love is doing is partnering with local legal nonprofits to give advice and education to people like Luisa and to potentially represent them in court. But for now, she’ll continue to wait.

MUSIC TRANSITION

Erin: A year after a federal judge ordered the current administration to stop separating parents and children at the US-Mexico border, families are still being separated.

In January, the American Academy of Pediatrics renewed its call for an end to family separation at the US southern border following a report showing thousands more children were separated than previously reported due to the number of other relatives — siblings, aunts and uncles, grandparents, cousins — who, just like Luisa, bring a child to the US without her birth parents and are then separated by immigration agents.

MUSIC

How do we approach these families seeking asylum with care and compassion? It’s a question we’ve been asking ourselves. Even within Preemptive Love, our team is scattered on the political spectrum. But what we can all agree on? Every single human deserves dignity and respect. We have to model what it looks like to listen. Because love crosses borders. And as the crisis evolves, this is what it boils down to: Families are risking danger, desperately trying to find refuge. And we can be the people who choose to love anyway on the US-Mexico border.

We’ll be right back.

SHOP AD

Jose: In 2001 my entire family migrated here. We crossed the desert, like many migrants did, and seeing the news, even today about families, crossing and family being separated and being held in cages is painfully sad to me, it really does cause you know, sort of physical pain to, to see photos and read about these, these things that are happening, you know, in the south people calling them concentration camps. And I think they are that and just to think that that could have been, you know, any, you know, it could have been in myself being separated from my parents it could have been any one of my family members.

Erin: That’s Jose Chiquito. My colleague Kim Mireau sat down with Jose in Indiana, where Jose is a college student.

Kim: Want to start out with who you are, and what you’re doing here, in Goshen? [laughter]

Erin: Jose’s parents are from a small state in central Mexico. His mom was a city girl–his father a village boy, the son of a cheesemaking family. They met when he was selling cheese in the city. They married, had Jose and his sister, and realized that raising children in the crashing local economy was hard. Impossible, even. The agricultural sector was getting hit, and the effects reverberated everywhere. His parents couldn’t afford diapers, medicine, and sometimes even formula. His father, in his mid-twenties, migrated north for work. And soon, Jose and his mother and sister followed suit, crossing the desert into the US.

José: I grew up in Goshen, since I was three. And I always knew I was undocumented. And, and that was somehow normal.

Erin: We asked him what it was like to bear the invisible “undocumented” status label. It wasn’t a label he chose for himself, but it was always there.

José: My dad for maybe three or four years after we arrived to the US, he began selling cars. He became associated with a car dealership with one of his friends and started buying and selling cars. He started with one car and saved up money still worked at a factory eventually had a good enough business to fully do car business. Used cars. And yeah, it was especially hard for us in the recession, because nobody wants to buy a car.

MUSIC

José: It didn’t really matter much. I mean, other than like, you know, we’re driving and there’s a cop behind us, or there’s, you know, police. There’s this constant fear of being pulled over while driving. And it happened to my dad several times, because he drove basically, for a living, he would go to car auctions in the area, sometimes as far as Milwaukee, or Pennsylvania and driving without a license because Indiana does not give licenses to undocumented people.

So there were definitely a few scares and instances where my dad did get tickets, but he was fine, miraculously. Um, so there’s this sort of fear of authority, of police authority.

But it doesn’t really matter until, like, the first time it mattered to me was in middle school.

MUSIC

Erin: As a young student, Jose learned about a statewide scholarship program. His teachers explained that if he maintained high grades all the way through high school, he could be eligible for a full-ride scholarship to college. In fourth grade, he started making goals. His parents were proud of him, but they didn’t speak English, let alone understand the inner workings of the education system. It only propelled Jose to work harder.

Jose: When we go to this meeting, in middle school, we’re, oh, fill out an application for the 21st-century scholarship, I had heard about this, I’m like, Oh, hey, tell my parents and I’m excited. We go there, we get to a part in the application, were asked for a social security number, and my moms like you can’t apply for this, you don’t have one, I’m like, oh…and we go back home. And it’s it was quiet devastation for me, because I knew. But somehow I didn’t realize it would matter so much.

Erin: The first version of the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act was introduced in 2001. As a result, young undocumented immigrants like Jose have since been called dreamers. Over the last 18 years, at least ten versions of the Dream Act have been introduced in Congress. They all would have provided a pathway to legal status for undocumented youth who came to this country as children.

But despite bipartisan support for each bill, none has become law.

José: That’s when I realized that it’s so not fair. Right. And so that, that stayed with me through high school, and until then, immigration became more present in my mind. I became aware of politics, and immigration, because it’s necessary, and because everyone in immigrant community needs to know about it. And we care because of the factors immediately. And then, you know, there’s more talk about DREAM Act, and everybody’s informed of what it is more or less, and I am able to be more informed because I can read, I can watch, you know, English, and we learn about how US politics work in school. And so I’m a little more literate in that. And then my family comes to me and asks what is happening. I feel a responsibility to learn and help my family.

Jose: At the time, I’m not an age to qualify for DACA – for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. But within a year, I qualify, and I get the status and I remember the day that I was like, in the car, and that we heard, heard on the radio, and my dad was so happy, we were driving back from a car auction of all things, and he was driving and he’s like, you’ll be able to drive legally.

MUSIC

Jose: And that’s important and go to college. And that was the thing that I was thinking about the most, go to college and having it be easier to get an education and a career perhaps. And then I felt that I could have a normal existence, and not hide the fact that I was undocumented with, with friends in school, you know, they talked about college and about these different things that I couldn’t be part of. You know, because of my status, I would hide and kind of pretend that I didn’t matter. But it always, it always does.

MUSIC

Jose: And middle school and high school students don’t understand that, you know, if they don’t, if they’re themselves are not undocumented, they don’t understand what that is, and why people can’t easily be US citizens. So it’s easier just not to talk about it, and pretend that you are a US citizen because really, your peers wouldn’t understand otherwise.

Erin: As a kid, and later as a teen, Jose was like many of us at that age–hoping to fit in. In his Latinx circles, talking about being undocumented wasn’t taboo, it was just part of life. But at school, it was a different story.

José: It becomes difficult and awkward to talk about it with people who don’t understand and who could be…who could just have very insulting responses to what you have to say, into your own story. So you avoid that. I did feel like I fit in pretty okay, in, in high school. Um, I was, well,

I had a lot of acquaintances. And, um, but yeah, that was just not something that I shared. People wouldn’t typically ask.

Erin: Immigration is a complicated topic, even for adults. Some of us are afraid to say the wrong thing. Others of us are afraid of those who are different. But listening to people like Luisa and Jose is a good start, because stories connect us, erasing the lines between us vs. them.

But then what? Where do we go from here? How do we broach a topic so often filled with political vitriol with our family members? With our kids?

MUSIC

Laura: When we talk with our kids, we make sure to emphasize that a lot of the people that are coming are mamas and papas, and nana’s and grandmas and grandpas, and aunts and uncles. And we try to put it in terms of relationship because our kids have relationships with, their parents and their grandparents and aunts and uncles. So that’s something they can understand. They love you, and they care for you, and so they will do anything for you. So we try to put it in relational terms for our kids.

Erin: That’s Laura Pontius. Laura is an immigration attorney and educator, who lives and works in northern Indiana. Laura is also a mom, whose work with clients around the world informs the kinds of conversations she has with her children.

Laura: I have two daughters. And they are seven and four.

Erin: Seven and four? So are they too young to be hearing about what’s happening in your country with immigration? Or are they picking up on that?

Laura: My kids aren’t really exposed to Nightly News. But to answer your question, no, I don’t think they’re too young. We do talk with them about immigration, mostly because it’s what I do for my work. And so a lot of times when we talk to them, we talk about what I do.

And we have been talking with our seven year old a little more about some of the recent issues that have happened at the border, and kind of talked with her about some of the changes that have happened, that affect, you know, the work that I’m doing and the people that I’m working with. So we’re able to have more in-depth conversations with her just because she’s older.

But with the four-year-old, we, we kind of tried to balance what we share with her. And then also every child is different. So, you know, my seven-year-old is, is very empathetic and cares very deeply about other people. And so when we share with her, we try to kind of give her the tools to navigate what we know she might be feeling with the realities of the situation.

Erin: What kind of questions does she ask you? In these conversations?

Laura: I represented a family earlier this year, that was claiming asylum from a country in Africa. And we had a time where she actually was with me when I was meeting with them. We were just doing a brief meeting. And so I had her in tow with me.

And so I just shared with her, you know, this is why this family came to the United States, and this is what I’m doing to help them. The paperwork…and, you know, the process to go through to be able to stay in the United States is very complicated, takes a lot of papers. And I show her my files, and I say, you see how much paper this is? Like, not everybody can navigate this process on their own.

And so she asked questions, in the midst of that case. Like, where did they come from? You know, we told her, it wasn’t safe for them to live where they were living. And so they chose to come to the United States, because it was safer here for them for their particular situation.

And so she would ask, “why wasn’t it safe?”. And their particular asylum claim was based on religious persecution. And so we thought we explained to her, in the United States, we’re really lucky, because we can believe what we want to believe, we can say whatever we want to say, we can have an opinion about anything. I tell her your favorite color’s pink, but my favorite color is red. And we can have those choices. And we can say them as loud as we want, wherever. But not everybody can have the same freedom in other countries.

And so you know, just kind of explained to her that we are really lucky to have those things here in the United States. And that people want to be able to live in a place where they can believe what they want to believe.

Erin: Laura and her family live in a rural area near farmers. This has given her the chance to talk about one of the causes of migration that isn’t talked about as much as it should be.

Laura: My husband is a professor of sustainability. So a lot of times we talk about some of the reasons why people come and how recently some of those things, reasons are changing because the climate is changing.

So a lot of people that are in Central America, or kind of around the equator area, they’re finding that they can’t live in the areas that they have always been able to live. And so we talk about, you know, we live out in the country, we live by farmers. We talked about how, you know, these farmers, it’s been raining, and it’s been sunny, and you see how their crops are growing. And so they’re able to have money to feed their family, because the weather is good here for them.

And how it’s not that way in other parts of the world. So they’re farmers who depend on the rain and the sun and the weather to be a certain way. They haven’t been able to provide money for their family to eat and to live, because the weather is changing.

So, you know, we do also try to not make it all doom and gloom for them. But just kind of give them tips about how, you know, all of these things are connected. Globally, in fact, it’s very connected to our actions and our choices that we make day to day, in our lives.

Erin: I asked Laura to tell me about the language around the immigration issue. Both as an attorney and as a compassionate human, Laura knows the importance of language.

Laura: in the immigrant advocate advocacy community, we always use the term undocumented versus illegal. You know, from our perspective, illegal describes not a human, but an action. And that a human cannot be illegal. A human can be without papers or without correct documentation. But that calling a human illegal is very degrading and takes a lot away from that soul and that person’s worth here in the world. From the legal standpoint, unfortunately, there is a lot of legal terminology still in our Immigration and Nationality Act that I consider derogatory. So I tend only to use it when absolutely necessary when writing legal briefs, but for the most part, you know, when we’re referring to clients or immigrants who are coming from other countries, we never use the word illegal.

People from El Salvador, from Guatemala, from Mexico…the gang violence has gotten to a level where it’s just an epidemic. And it’s very dangerous, especially to be a female, or to be a child in those areas of the world right now. A lot of it has to do with climate change too, and causing, you know, everything is connected. So it’s not just gangs being gangs. It’s there, you know, economic forces at play, that are based on the environment, and based on various trade agreements, and, you know, cross border agreements as well.

MUSIC

Erin: More immigrants live in the United States than any other country in the world. Today, more than 40 million people in the US were born in a different country, accounting for about one-fifth of the world’s migrants.

Laura: We feel that education and knowledge is a really powerful tool right now for the immigrant community. There are a lot of myths and rumors going around in the immigrant community, but then also in the non- immigrant community about what is happening. And so we try to just equip people with truth, and facts and figures. And sometimes it’s boring, but most of the time, I think people walk away feeling like, ‘Oh, I’m glad to have that information’.

END MUSIC

Erin: Visit this episode’s show notes at preemptivelove.org/podcast for more tips for talking about immigration with your family, statistics and studies used in today’s episode, and links to Jose’s personal podcast. You can also download free Love Beyond Borders wallpapers for your phone.

In our next episode of Love Anyway, we explore involving children in their community in ways that matter, as we follow Preemptive Love’s key relationships officer Diana Oestreich and her sons as they attend a vigil on behalf of families at the border. We’ll hear from a child’s perspective their family’s commitment to community involvement and navigating hard topics as a family.

Connect with us and learn more about what we do via @preemptivelove on Instagram and Twitter. Use the hashtag #loveanyway to give feedback or start a conversation.

I’m Erin Wilson, and this is Love Anyway. Thanks for listening.

END MUSIC

The Love Anyway podcast is written and produced by me, Kayla Craig, along with Ben Irwin, and Erin Wilson. Skip Matheny is our digital production director. Jonny Craig is our audio editor. Our audio is mixed and mastered by Dylan Seals. Jeremy Courtney, Jessica Courtney, and JR Pershall are executive producers. Special thanks to Billy Price, Jose Chiquito, Kim Mireau, Eileen Rose, Laura Pontius, and Luisa—whose name was changed to protect her identity. Our theme music is by Roman Candle.